The Hundreds X Garfield is sold out in our Online Shop, so here’s a list of global stockists that may still carry the collab in-store and online.

My father had every Garfield book every released, or nearly every one. Those narrow little volumes were so distinctive, printed to contain one strip stacked on top of another on each page. They took up an entire long shelf in our attic.

I used to sit in that attic and read scores of them. Cross-legged or even laying on my stomach alongside the dusty particle board, I had a world of my own wrapped around me. I always wanted to escape and be alone to read, and this was the perfect place. And Garfield was so easy to devour that it was almost like watching television.

But one day my quiet little world was disrupted by an unearthly voice, and a crack opened up into the great and yawning beyond—and it was all Garfield’s fault.

Garfield never has a narrator. But he does today.

Jim Davis’s serial strip is not known for being deep or challenging or existentially harrowing. You don’t read Garfield to have your mind blown. The strips unfold along very predictable, repeated gag vectors: Garfield is cruel, lazy, and self-indulgent; Jon is emotional and vaguely pathetic; Odie is dumb; Nermal is cute and annoying.

The world of Davis’s comic strip is tiny, and Garfield’s cruelty lacks real consequence, so it’s funny. The characters have just enough pathos and real feeling to keep you interested. Their responses drop like punchlines. The arcs and departures are non-threatening, and then everything returns to normal.

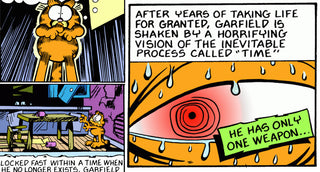

But one evening locked in that attic, I stumbled across this strip:

Immediately, the world of the comic feels different. The background is shaded darkly, and there’s actual 3-D perspective in the last panel—rare in Garfield-land. And then, the arc: there’s no neatly parsed joke, not even an attempt at one. We’re left with an unsettling open question, and absolutely no context to help us feel a sense of emotional resolution. For maybe the first time ever, Garfield has thrust us into the unknown.

This is nothing compared to what happens next.

That dramatic vanishing-point perspective is back again. The camera lens is tilted, we’re disoriented, and strange shadows play around the familiar furniture. Then in, the last panel, a disquieting voice breaks into our world. Garfield never has a narrator. But he does today.

Decay is real here, in a way it isn’t in the rest of the Garfield universe.

On the surface, there’s nothing wrong with Garfield being alone. Jon leaves the house all the time. Maybe he took Odie; maybe they went to the park. This situation really isn’t that bizarre. But that narrator’s voice is bizarre. Who’s speaking to us? And why?

The next strip made my hair stand on end, reading alone in my parents’ house. Even now, I get goosebumps on the last panel.

Here, we’ve descended fully into the nightmare zone. Those alien, deeply-textured shadows have dominated the once-bright world of Garfield, and that last shot of the house buries our feeble hopes: Jon is not at the grocery store. Odie is not at the park. Something truly terrible is going on.

When I processed that last panel, as a kid sitting there in that dusty attic, the world slowed down around me. Suddenly, I wasn’t sure if my parents were at the grocery store either. The room was quiet, like a muffled recording studio. Maybe nobody else was there. Maybe, outside those walls, an empty landscape stretched out in all directions.

Decay is real here, in a way it isn’t in the rest of the Garfield universe. We’re used to smooth surfaces—the same furniture, the same flat, brightly colored walls. Jon’s chair never frays or leaks stuffing. The paint never peels.

Not so in this new realm.

Davis has catapulted us into the abyss of time, where things change, everything falls apart, and nothing is permanent. In a way, he’s created the exact opposite of a Garfield strip. His tiny, comforting, tightly constructed world gapes wide, utterly violated, and we stare instead into the infinite beyond.

But what’s this? What’s that sound, in the last panel above? Does some new horror await us, or are we to be drenched in the comforting balm of a punch-line at last?

For a moment, we felt relief. The arc could have ended right there after that first panel, with some calming platitude about how we should value those close to us, or how it was all a dream. It still wouldn’t be a standard Garfield strip, certainly it would remain a deeply troubling node in our favorite orange cat’s otherwise imperturbable journey. But at least then we could dismiss it. At least then we could tell ourselves it made sense.

But no. The football, to mix references distastefully, is yanked away from us. There is to be no mercy here, and we begin to wonder how long this is going to continue, and what the point of it all is. What on earth is our spectral narrator communicating? Is this narrator Jim Davis, reaching into the strip like a god, trying to tell us something? Is god lonely?

The final strip provides us with answers, of a kind. But they are not comforting answers.

In the first panel, our previous fears are confirmed: we now inhabit the crippling domain of time, where all things crumble, wilt, and pass away into decrepitude. The comforting walls of Garfield have been stripped away, one of our few safe havens gone. We have been thrown from the nirvana of endless lasagna jokes into the samsara of inevitable wasting and death.

Finally, in the center split panel, Davis rescues us from this hell. But is it really a rescue?

Garfield provides us with a happy ending through sheer denial: he convinces himself with blind will that none of this is happening. His hypnotized stare in the bottom center is proof: He’s maintaining his old reality by forcing some sort of self-preserving hallucination.

Far from waving this explanation away, far from giving us the comfortable wake-up ending we hoped feebly for earlier in the arc, the narrator’s denouement endorses, practically celebrates Garfield’s delusion. We’re told that imagination is a powerful tool, and that it can convince us of anything.

Davis has catapulted us into the abyss of time, where things change, everything falls apart, and nothing is permanent.

This raises serious questions about the nature of Garfield, the strip itself, the whole institution. Is Garfield repetitive, happy, and easy because it’s a knowing and purposeful retreat from reality? Is it Jim Davis’s direct and deliberate attempt to stave off existential horror and to freeze the merciless ravages of time?

When I had my first moment with this strip, I was sure I was alone. Did anybody else even remember this happening in Garfield? This feeling made the memory surreal, and when I went looking for this strip, I wasn’t even sure I would be able to find it—maybe I dreamed the whole thing, or maybe it belonged to one of those half-pretend worlds we leave in the mist when we become adults. But I found out during research that countless others had had the same experience—that this strip is well known within the Garfield canon, and that mystery has swirled around it since its release.

We were all horrified, and we all felt it was some kind of twisted violation of the basic social contract implicit in Garfield. This wasn’t just scary, it was against the rules.

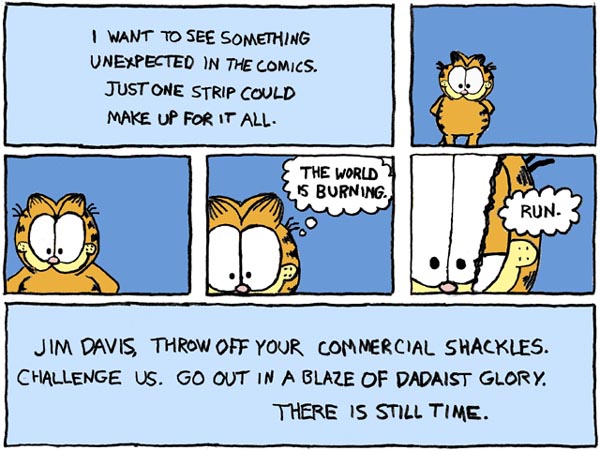

An XKCD strip about Garfield.

When we look at this arc, it seems inarguable that Davis knows deeply and exactly what Garfield is and how it functions in society. XKCD’s Randall Munroe urges Davis to “go out in a blaze of Dadaist glory,” but Davis already did, way back in 1989. Projects like Garfield Minus Garfield and Lasagna Cat turn the much-loved strip into a bleak, surreal, post-ironic desert, but Davis saw those qualities and drew them forth explicitly almost three decades ago.

I looked up from the book and around me at the dusty attic. I inhaled the smells of my family’s yellowing photo albums and the kindergarten art projects around me. I lived in a happy home as a kid, in a small town, with relatively predictable and small cycles of joy and disappointment—I spilled the milk, I got an A, Christmas is here.

But the moment I saw that third panel, the one with that dilapidated house, I knew a different kind of life was beginning for me. Something great, terrible, and ineffable stretched out before me. I had to change, I had to grow up, and someday I had to fall apart. Only Garfield gets to stay the same.

***