Antwerp-based artist Brecht Vandenbroucke grew up on an isolated farm in a small village in Belgium. There was no TV in his house, so pop culture trickled in through his four older brothers. He discovered cartoons through the video game magazines his siblings brought home, and would look at the images and make drawings inspired by them. Today, his vibrant illustrations are still rife with pop culture—from The Flintstones to Felix the Cat — but with a satirical bent. In an acrylic painting that references The Simpsons‘ opening sequence, Bart is naked and chained to the wall, and repeatedly writes “punishment is my reward” on the chalkboard. “I try to use my tools as best as possible to make the audience think or feel something,” says Brecht, “hopefully with some humor in it too.”

Shady B*tch, his ongoing one-page comic, is evocative and hilarious too: “It’s about a big bearded character that yearns for acknowledgement, adoration and love,” Brecht explains, “but has no idea how to get all of those things and acts out like a big child.” In one of the strips, for example, the police catch the clueless character spray-painting “fuck you” on a wall. “What are you doing?” one cop asks. “I’m writing a movie script,” the man-baby answers in all seriousness. Then, throughout his journey to jail, he continues to pepper the cops with wide-eyed questions like “Am I being discovered?” and asks if his prison uniform is his “costume.” “Drawing for me is trying to communicate my own thoughts, but still share a perspective and connect with other people,” says Brecht, who also discusses his influences, artistic style, chaos, order and the art world in the following interview with The Hundreds.

Music, Brecht Vandenbroucke

ZIO: When did you decide to become an artist?

BRECHT VANDENBROUCKE: I never really decided—making things was something I always did. It’s the one constant thing in my life. I have always created, going from making figures in clay to clothing, drawings, short animations, etc. It was more an unexpected awareness that the label of artist could be applicable for some of the things I was doing. I still never really think about it too much. I’m still not sure what I am.

Who or what have been your biggest influences?

So many artists. Again, when I was younger, the art of stickers, TV shows, video cassettes and the art of video game boxes by artists like Greg Martin were very influential (although, unfortunately, they were mostly uncredited, so I found their names only years later, once the internet was more established). And of course, there was a lot of Simpsons. Later, when I went studying, I was really into Fernand Leger, Jeroen Bosch, David Shrigley, the collages of Max Ernst and Eduardo Paolozzi, and of course Belgian artists like Hergé, Walter Van Beirendonck, and René Magritte. I also loved the work of Saul Steinberg, Alexander Calder, the songs of Tom Waits, paintings and drawings by Helge Reumann, Frida Kahlo, Hockney, Neo Rauch, Philip Guston, Tomi Ungerer, filmmakers like Hitchcock, Lynch, Jacques Tati, Jan Švankmajer, and of course the German Illustrator ATAK—he was hugely influential for me as a teacher. He was actually the reason I started painting. In the recent years, I learned to appreciate American comic artists more, older stuff like Frank King, Gluyas Williams, Ernie Bushmiller, and Abner Dean.

Did you start out making satire or did that develop over time? Why is it important to make critical work?

I don’t know if it’s important, but I do know I have a critical attitude and I’m always trying to work on it, be it to make it sharper or soften it down. Sometimes, criticizing stuff can be exhausting to me, so it’s definitely not something I’m constantly on the look out for. Most ideas just come to me. It’s about communicating a point.

Drawing for me is trying to communicate my own thoughts but still share a perspective and connect with other people. It’s a thin line to walk: Still images like paintings are flawed and limited, they only show one small aspect or idea and they don’t move or make any noise. So it can be dividing to be critical. Not everyone is going to like everything you do. So I try to use my tools as best as possible, to make the audience think or feel something, hopefully with some humor in it too.

The Division, Brecht Vandenbroucke

What issues are most important to you to address?

I probably haven’t addressed it in my work yet, but I think there is a lack of responsibility in this world. A personal responsibility for our own actions. But that’s a very hard thing to do in a drawing, or make it funny because it’s quite moralizing. For me, it’s better to research that in a story for example, and that’s what I’m planning to do.

I think we all need to start looking inwards, at ourselves and what we are doing wrong instead of continuing the (what I call) name-shame-blame-game. In other words, pointing fingers at others, which is very popular online. We are all flawed. We are all trying. We are all struggling. We are all on a quest for happiness. Most of us are really doing our best. I think we are culturally afraid of growing up, making the tough decisions, and in that way we avoid having any responsibility for anything at all. I try to look for what I am doing wrong and how I can be better. I think it’s the only way to make this world a better place.

“I think we are culturally afraid of growing up… we avoid having any responsibility for anything at all.”

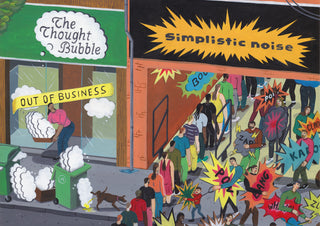

Many political cartoons are somewhat simple, artistically speaking, in order for the message to be easily understood. Why create images with a lot happening visually?

I am interested in chaos and order. I believe in the balance between both, like in a Yin-and-Yang symbol, always communicating with each other, a constant dialogue between two opposites. That’s where I believe the truth can be found—in the middle. So I think freely and then I try to put my thoughts in order. That’s why I sometimes make bigger and busier paintings. I see them as mood boards for my comics. It’s part of a dialogue I have with myself, where I try to conquer new territory and draw new themes I haven’t touched before, but on my own terms. It’s like a sketch that turns into a work of its own. It’s a way of working that’s very related to collage, of which I made a lot in my early 20s.

It also might have to do with being from Belgium. Like I said earlier, I do love painters like Bosch and Brueghel. They tend to fill up their images quite well. I am sometimes possessed by the idea of “horror vacui,” the fear of emptiness. Beginning is hard on a white page, but once I start I sometimes cant stop adding things. I even made a zine about it, with that name.

Fathers, Brecht Vandenbroucke

What made you want to confront the art world in your book?

Postmodernism confuses me sometimes. I am always trying to get to a bigger truth or bring it back to an overarching narrative. I do make narrative and figurative art after all. That’s why I decided to make “White cube,” which actually started out as a zine I did when I just got out of art school. In these comics we follow an ambiguous duo called the aesthetic critics, through a trip in the world of art, design, dance, architecture, etc. They encounter all kinds of art and give it a thumbs up or a thumbs down and interact with the art in a humorous way. I made a humorous book to figure out what modern humans could learn from art and all of its criticism and all its confusing aspects. I was trying to make sense of it all.