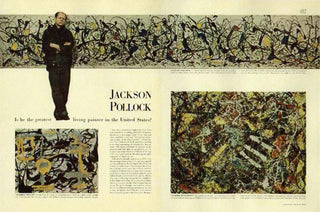

“Jackson Pollock. Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

This question, posed in the iconic 1949 Life Magazine feature, catapulted the virtually unknown (at the time) Jackson Pollock into American pop culture, and consequently, the world. Pollock’s story is one of genius and sorrow, explosive achievement and demise—the makings of a classic tragedy. But before we get into the details, let’s return to the beginning.

Jackson Pollock’s Life Magazine spread

Jackson Pollock was born in Wyoming in 1912—the youngest of five sons. He spent the majority of his upbringing in Arizona and California, and moved to New York City in 1930 to pursue art, learning under Thomas Hart Benton, a leader of American Regionalism within the art world, at the Art Students League in Manhattan.

From 1938 to 1942, Pollock worked for the Works Progress Administration, a federally-funded agency that emerged as a result of The Great Depression—aiming to give unskilled and unemployed Americans an opportunity for work. Pollock was specifically involved in the “Federal Art Project,” which gave money to out-of-work artists to create murals, sculptures, and paintings and provided some semblance of stability and relief post-depression. This was especially needed in Pollock’s life, as the artist dealt with alcoholism early in his career, with some historians even speculating that Pollock suffered from bipolar disorder.

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner

During this period, in 1942, Lee Krasner came into Jackson Pollock’s life. An artist herself, the couple met while exhibiting their own respective works in New York. Krasner immediately saw Pollock’s expansive potential, and even followed him back to his apartment the evening they met. She is arguably the most important figure in Pollock’s life. A relationship ensued, and they later married in 1945, leaving the bustle of the city for the peace and calm of East Hampton to continue furthering their artistic endeavors.

Lee Krasner was an incredible supporter and influence for Jackson Pollock’s work. As a critical artist herself, she was described as the “mastermind behind her husband’s success” by art historian Anna C. Chave. Art dealer John Bernard Myers was also quoted stating that, “there would never have been a Jackson Pollock without a Lee Pollock, and I put this on every level.”

Pollock’s first introduction to liquid paint happened in 1936, during an experimental workshop led by Mexican muralist, David Alfaro Siqueiros. It sparked his interest in liquid paint pouring, which eventually turned him to the “drip” technique that he is so well-known for. He moved from easel to the floor, stretching out rolls of canvases, making sure he was well-acquainted with every fiber, every drip, every stroke. “On the floor I am more at ease,” he said. “I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.”

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950

From 1947-1950, known by many as the Drip Period, Pollock’s work skyrocketed. His high-energy canvases and fluid, abstract paintings became widely admired in its ability to challenge what art was. The painting became about motion and action, a unique dance solo around the canvas that breathed life into the work. Galleries, critics, and magazines flocked to him, eager to witness this new phase in American art. “I have no fear of making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through,” Pollock said. His method of using his entire body to paint became a study of movement and control—chance and intention. He created some of his most famous pieces during those years, including Number 5 and Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), and was widely celebrated within the art world as a key figure in its newest movement.

Despite the support of his creative wife, and the explosion of success that came with Pollock’s drip paintings, the artist continued to struggle with his alcoholism, causing a huge strain on his relationship with Krasner. Just as quickly as Pollock rose to notoriety, he stopped—abandoning his paintings. He felt that he lost touch with his work and ceased utilizing his drip style. Simultaneously, he began an extramarital affair with aspiring artist Ruth Kligman in 1956; he was 44, and she, 26.

Krasner, engulfed in anger at the discovery of Pollock’s infidelity, left the states to see friends in Europe during the summer of 1956. Ruth Kligman consequently moved into Pollock’s East Hampton home he shared with Krasner. Their relationship was mere months old.

Ruth Kligman, left, and Jackson Pollock. Photo: Vanity Fair

On the evening of August 11, 1956, Pollock, Kligman, and Edith Metzger—a friend of Kligman’s—got into Pollock’s car for the final time. Pollock had spent the entire day drinking, and took a sharp turn on Fireplace Road in East Hampton, sending the vehicle and its passengers flying. Kligman was the only survivor.

Pollock leaves a legacy of innovation and genius, countered with destruction and self-loathing. As writer Will Blythe wrote in Mirabella Magazine in 1999, “Hold his story up to the light, turn it whichever way you will, and it can serve as an object lesson for almost anything—the ravages of demon rum (or six-packs all the livelong day), the devouring of the artist by the wolves of commercialism, a foreshadowing of the perils of celebrity culture, the comedy of psychoanalysis in its American heyday, and on and on.”

***

The Hundreds X Jackson Pollock Studio is available now at flagships, select retailers, and our Online Shop. See the lookbook HERE.