“So we had to have flyers, and you had to call the number to get the address,” Patrick Moxey explains about promoting hip-hop parties in early ’90s New York. “That’s how you knew where the party was. That’s how we made sure the people we wanted to be there were there, and the people we didn’t want to be there, wouldn’t.”

It was the hightop-fade late ’80s, and the Ninja Turtle ’90s. New York City was in the last throes of a world without the internet. It was tactile, boot straps, industrial, and the place to be for the nightlife scene. The people came from everywhere, with different denominations of money in their pockets. But money wasn’t the matter. The matter was hip-hop and the party scene that was spreading its graces to the cool kids.

Photo: factmag.com

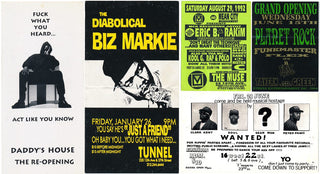

In the new book, No Sleep: NYC Nightlife flyers 1988-1999 by legendary DJ Stretch Armstrong and Evan Auerbach, that scene is offered in a retrospective of colorful club flyers and various interviews from the DJs, MCs, promoters, who made it all happen.

The flyers sponsor a narrative that functions the way a strong author sets a scene with prose. You’re pulled from your perch onto the page, down into the world where that club night is waiting, and you’re in-the-know enough to make it past the door guy.

Front of Black Sheep Live at Building flyer, 1990

And it’s not the varnish of crafty layouts that hooks you, but the DIY sensibility of it all. The invites—which often served as tickets to these functions—were cut and paste photo copies with event info sharpied in. They were hand script appropriations on card stock. Now, they are time capsules of guerilla graphic design before Photoshop. Frankie Inglese explains, “I’d find an image and my man Richie would work on it on a computer which we’d rent by the hour, and then we’d take a design to a print shop. The design would be on a big floppy disk!”

Front and back of Supreme New York Launch Party flyer, 1994

The scene is illuminated by more than just the spectacle of flyers—it’s the people chronicled that are its moving parts. The excerpts of prose follow those who were responsible for crafting those flyers, curating those crowds, and booking those venues. Whether in a basement nightclub or an old olive-oil factory, those DJs and promoters were united by a pulsing vocation to throw the best new hip-hop functions. The DJs carried duct-taped milk crates of records onto planes. The promoters carried 20,000 pounds of sound equipment up five flights of stairs, only to tear it out the following day.

Occurring time and again in No Sleep’s pages are mentions of hip-hop touchstones and legends from the time before streaming radio. The likes of LL Cool J, De La Soul, and A Tribe Called Quest all get airtime, but what’s more nostalgic are the recurrent recollections of acts from the Yo! MTV Raps generation like 3rd Bass, Fab 5 Freddy, and Kid Capri.

Photo: okayplayer.com

A common thread from everyone’s recollection is the sheer diversity of the scene in those club days. Parties weren’t packed with those supposed to be found in the hip-hop nightlife, but of folks from various scenes who wanted to celebrate hip-hop. Peter Sabilia recalls, “New York’s clubs celebrated our differences, heralded our creativity, and rewarded our love of life. They had the magic to transform us into whoever we wanted to be or imagined we could be. Once you passed through those doors, you were acknowledged as a member of an elite crowd.”

No Sleep showcases an ardor for a heyday of the New York party scene that is bookended by Bret Easton Ellis on one end, and the internet on the other. A reader can only pine for what now seems like a mythical landscape: being a cool kid before social media; a time when MCs wrote their own raps. One can close their eyes to dream about it, but you’re encouraged to get No Sleep.

***

Pick up a copy of No Sleep HERE.