Back in 2010, when I began to take pictures of graffiti found on the trains I was taking to go to college, I thought I was the only one that ever came up with this hobby. I was naive, or rather, entirely clueless. Only after getting to know some writers and Googling things, I found out more about the roots of graffiti/trainbombing culture, and eventually about a legendary woman who was already documenting all of it in New York during the ’80s. I never thought I would actually meet her one day and have the opportunity to confront myself with someone that enjoys the discovery of a painted train as much as I do.

As soon as I knew New York photojournalist Martha Cooper was going to set foot in Italy, I had to do all that was necessary to meet her. That involved a trip to Venice, where we first met and where she signed my copy of Hip Hop Files two hours before catching a flight for Tahiti. So I let her go with the promise to see each other again in Gaeta, southern Rome. Ten days later, she landed back in Italy and I traveled half the length of my country by train to reach her. During those waiting days, I researched as much as I could because I didn’t want to feel unprepared. Reading Hip Hop Files was delightful and helpful in finding the right questions I knew I wanted answers to. As you will read below, Martha is the best source for a living history of graffiti documentation – she’s fearlessly delved into it since ’70s and ’80s. Find out what sparked her involvement in the culture, why she prefers it illegal and self-driven, and why it’s difficult for graffiti pioneers to enter the often confusing space of the art gallery.

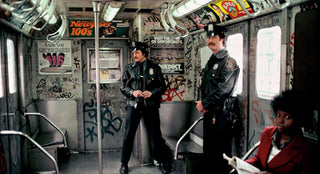

Photo by Martha Cooper via Fallopia.com

SPRAYTRAINS: What was the moment you realized you were going to be in the middle of a movement bigger than you ever thought? What were your feelings and what happened next?

MARTHA COOPER: I didn’t understand how big it was until around 2004 when I published a book called Hip Hop Files and the author, Akim Walta—who is German and published the book—took me to Europe. At that time, there was a pause of interest in graffiti in America. Subway Art was an old book and people weren’t really buying it anymore. But when I went to Europe, I was very surprised to see what a vibrant culture it still was. All of them: hip-hop, graffiti, b-boying; the whole thing. When we went on the book tour to 18 different cities, people knew who I was and that’s when I was like, “Wow! This thing really happened.” I didn’t understand it until then. That was a long time—the first book was published in 1984 and I didn’t go to Europe until 2004. That’s 20 years later.

About what happened next: I got interested again and jumped back into it. I’ve sorted jumped out because I needed to make some money, I was a freelance photographer and I was working very hard on my photography career and that didn’t really include hip-hop and graffiti at that time. Even now you can’t really make money taking pictures of street art and graffiti. But when I saw how many people were interested I thought well, I am going back into this. I really made a decision of jumping in: let’s do this again. Just when you thought it couldn’t get any bigger, it kept expanding and so here I am in Italy, travelling around and living a pretty interesting life because of what happened next.

Photo of Martha: oldskull.net

Graffiti has such an irresistible force. What do you love about it and what would you leave?

For me, the illegal part was always the most exciting part, and what really interested me was the idea that kids would go to great lengths to do art and that they were doing art for each other – mostly adults didn’t understand that. So I thought that I was led into a secret world and it was an underground world. Now it’s an above ground world. Although, of course, there is still a lot of illegal graffiti happening… Recently, what country was I in? I think Brazil—we went to a yard over there and we got chased out of the yard. That was kind of funny. We went in, kids were painting the trains, and next thing you know, these cops came along on a motorcycle and we had to climb over a fence. And the fence was very high. We climbed up, then I looked down and thought, “Oh my god, I can’t really jump.” So two guys helped me down. That was a little scary.

“FOR ME, THE ILLEGAL PART WAS ALWAYS THE MOST EXCITING PART”

Back to the question about what I would leave: I am not so interested in all the permission walls – I prefer the ones you don’t know about. For me, the exciting part is to be in the place and happen to come across a piece of art that you’ve never seen before. It can even be a really small piece of art, doesn’t have to be the whole mural. I am not saying that I would leave the big permission walls like in this festival, it has been great for me to drive around and look at the walls. But it’s not quite as exciting as walking down the street and seeing a piece by C215 like the one I saw arriving here in Gaeta. Than you have this feeling of discovery, which is different from having a catalog in your hands where you already see a picture of it. Although, when you see something in person, it’s more interesting, you see things differently from pictures.

…I don’t mind the commercial part of it. I think artists deserve to make money from their art. I think it’s funny when I see big companies trying to emulate the graffiti style, like faking graffiti lettering. That’s something I always laugh about and always take a picture of. I am not saying that that shouldn’t happen, but none of it has the same excitement as waiting for a train.

Photo: back2groove.com

Can you tell me a photography adventure that was intense and maybe involved some fleeing away?

I think the best adventure was when I went to the yards with Dondi because, until that time, I hadn’t been in the [train] yards. Although I’ve heard so much about the them, I couldn’t exactly imagine what he was talking about when he was saying that he was standing between trains—you know, like in the picture [below]. Remember, we are talking about the age before computers, so there were really few pictures circulating about trainwriting.

Plus, I didn’t understand how he could paint an entire car in one night! And even now, it’s amazing because when I see this people working on their walls, they can do it for even as long as a week! Sometimes they paint so slow that I think, “If this person was in the yard, they would have already been arrested.” Trainwriters paint freestyle. They also plan ahead about which colors they’re going to use and what they need for the outline and the filling… It’s really a mission. Going to the yard was so exciting and we had such a great night. After that, I went to the yards another couple of times, but nothing was as exciting as the first time. And the pictures I took weren’t as good as the ones I took the first time.

Of course for me, an adventure is not complete unless I have the good picture to show for it. The photograph for me seals the deal—makes it really memorable.

Photo: oldskull.net

What fascinates me is the DIY aspect of hip-hop culture at its beginning. Even if there were few resources around, people always seemed to make the best with what they had. How important is being autonomous to you?

The DIY aspect is really fascinating. Before graffiti pictures, I shot photographs of kids making their own toys and that was a thing that captured my imagination because they had such an imagination. I was always looking to see how they were playing and whether their parents were watching. I especially enjoyed seeing kids that were being adventurous, like jumping out of the window into a mattress. In NY in the late ’70s and in the early ’80s, there were these vast areas where buildings were burned down and the kids could just go into these buildings and make their club houses or whatever they wanted to do. It was before the age of AIDS. I think parents became a lot more cautious about letting their kids run on the street after that. People were thinking if you stab yourself with a needle you might die because of AIDS. So although there were many other drugs in NY at that time, I think in the early ’80s, for this matter, parents became a lot more watchful over their kids.

Hip-hop kinda grew out of this idea. A do-it-yourself culture that included music, dance, and art—it’s a complete culture. Actually, I was given a lot of freedom growing up myself. My parents didn’t keep a close eye on me. I could go wherever I wanted to go as long as I kinda came back for dinner. Without mobile phones, they just assumed I was able to find always my way home. When I was looking at these kids, I was remembering my own childhood. So at the end, autonomy stuck with me.

Photo: alldayeveryday.com

Assuming that perception is reality, do you believe people nowadays are more aware of the phenomenon of graffiti than they were in the ’80s? How about your Instagram followers?

Well, I think they are more aware that graffiti exists, but I don’t think they really understand what it is and I don’t think they are making a distinction between, say, illegal graffiti and street art. I have often heard legal walls being called graffiti. And you know about the exhibition Bridges of Graffiti, where we met? There was a big discussion about the use of the word graffiti to describe any part of it actually. Some graffiti writers, I call them writers or artists, don’t wanna use the word graffiti at all. They only want to call it art. And I mean, it is art whether is it legal or illegal, I would definitely say it’s art. It might not all be good art. There is good art and bad art. I would say if you are painting with a spray can, it probably falls under the broadest definition of art. I think most people aren’t making a distinction between somebody writing their name on a wall illegally and a permission wall as part of a festival. It’s kinda odd when you hear some of these very elaborate production pieces being called “graffiti.”

“MY INITIAL INTEREST IN GRAFFITI WAS THE FACT THAT KIDS WERE DOING IT FOR EACH OTHER”

About my Instagram followers, I don’t know if they are watching carefully. I try to make the distinction. For example, if it’s a graffiti piece I am going to write #graffiti. If it’s a street art piece I will use #streetart. If it’s a combination of both and the artist has a background in graffiti, I use both hashtags. But if it’s a solid graffiti piece, I am not going to hashtag street art. With every picture I upload I try to make a little caption with information. And I am always choosing what walls and other things I should post or not. If you look at my Instagram, I do not post every wall. There’s usually a reason, sometimes is that I just that I like the wall.

How does graffiti fit inside your daily routine in NY?

I didn’t used to always carry my camera around with me because cameras are so heavy. It just felt too heavy to always be carrying camera equipment around. Now, of course I always have my phone and I usually have a small camera too. I am more likely to take pictures of smaller pieces now, like, I got very interest in hand drawn stickers called slaps. I also did a book about them called Going Postal, photographs of postal stickers. The term going postal came from a post officer who went crazy and murdered lots of people. One of the reasons they didn’t like the title at the beginning. For me, it meant going crazy for the postal stickers, which you can get for free and people draw hundreds of them.

About my routine, I always keep my eyes open as said before, especially in NY since it’s a walking city. I take tons of pictures, but I post few of them. All is on my computer.

Photos: socialregister.co.uk

Are all your pictures well organized?

Uh, not very well. I organized them by folders. I have an NY folder, a street art one, and in it I have folders by artists. Then I have a stickers folder, which is organized by year. I am not good with metadata. I generally don’t add any information because the volume is too big! Who even knows what’s in there. Maybe someday I will give my archive to somebody to figure it out! …Bottom line, I am not really the person to ask about organization. Pfff, so terrible.

Do you collect art books, T-shirts, and other things? What’s the most valuable item for you?

I don’t generally buy a lot, but I do collect everything and now I am starting this library in Berlin and I actually gave them eight boxes of books. As I go along, I am collecting, for this project, posters, cards, stickers, and zines like the first African Graffiti zine that is just a little xerox. It’s going to be a permanent exhibition called Urban Nation. It’s opening in 2016 and I will contribute to the library section. Last year, I made three trips to Berlin and I might go again in June. I am supposed to look for rare things. So for example, later today I will call this guy, Andrea Nelli – I am trying to get a hold of his original book about NY Graffiti for the permanent library.

Wherever I go, I am trying to collect material for the museum. Back in NY, I have only one bedroom apartment, I don’t have the space. I do have storage space that I spend money for… It’s too hard to keep a lot of stuff. I am trying to find good places to put that stuff. And I really don’t want to sell what I have so I’d rather give it for the library collection.

…But back to the question: I kept things like a Keith Haring catalog that he signed. However, my photographs are my most valuable item! For me, I don’t think there’s anything else that’s more valuable than my own pictures. I also have many black books. Inside my black books, I have a few pieces that valuable for me. I don’t take it around, so I have many half-filled black books because I don’t wanna lose them.

My first black book has a Keith Haring piece, a Dondione, a little Basquiat, Crash, Futura, Daze, and all those early writers. This first black book is my most valuable item if we don’t take consider my photographs. Oh, and I have a nice painting from Os Gemeos they gave me of me sitting on a train holding a camera.

Photo: alldayeveryday.com

Since you have nursed the whole [graffiti and street photography] culture, what do the writers’ bench versus the art gallery world imply to you?

My initial interest in graffiti was the fact that kids were doing it for each other. They had their own set of aesthetics and they knew things, like if this person was a toy or if the lines where done correctly or not… I was interested in finding out how they were looking at these pieces, how they were judging – what they thought was dope, and what they thought was wack. All this was part of the excitement of figuring it out.

About the art gallery world – I don’t think graffiti translates that well into canvases. I think that when you are used to one: having to do something illegally and doing it at night and, two: doing it with your arm spraying in a free, fresh, and quick way because there’s the treat that you could possibly be arrested, it’s a lot different than being in your studio… I think it’s very hard for somebody that’s grown up painting large pieces to have to condense that onto a canvas. On the other hand, I think that if you can do it and people wanna buy it, that’s fine! I personally don’t buy canvas, I don’t own those canvases. I just have canvas that people give me and some of them are quite nice. But none of them are as exciting as seeing it on a train. I mean, if you were going to put the piece you saw on a train onto a canvas, it would be completely different.

“[NOW PEOPLE] ARE MORE AWARE THAT GRAFFITI EXISTS, BUT I DON’T THINK THEY REALLY UNDERSTAND WHAT IT IS”

I think the art gallery world, in some ways, is kind of sad because some of the earliest writers that were the pioneers are trying really hard to get into the gallery world and they just can’t because they don’t understand what it is. I mean, who can understand it? Surely I don’t understand it either. It’s a different world, the aesthetics are different and the people who are making the judgments are different. So you are making art that is supposed to hang on a wall, you have art critics that are going to say whether it’s good or bad, and these art critics are not your peers.

In my own photography, I don’t really want to be a fine art photographer. For this reason, for many years I said don’t want to do exhibits. I want to do books, I wanted to be a documentary photographer. Not something about making photographs and hanging them on a wall and then having to stand back and have people judge them as an art piece. At the beginning, this wasn’t my original intention. However, now a lot of people are asking me to have exhibits, so I am like, “Alright, why not?” I am also selling prints because I need to make some money. Originally, I didn’t consider publishing a book, but I was interested in magazines because I was more of a journalist.

Photo: concretetodata.com

What other forms of preservation of graffiti culture could we expect in the future?

We are preserving! Partly, what we are doing is historic preservation, so our archives are the best way to preserve this culture if they are organized, which, as we said before, mine aren’t that organized. I do think that photography, especially still photography, is the best way. One of the reasons why I liked to document this art is that I think it’s an excellent subject for still photography as opposed to video, which everybody is doing. Video is nice, but you can’t really study a piece in the same way as you can with still photography. Back in the day, kids would see tiny snippets of videos coming from NY. Then when we published Subway Art, and the attraction of the book wasn’t so much about the fact that we had documented the scene, but the fact that kids could study the styles, they could see the 3Ds, the outlines, and all the little things that you miss if you were just watching a video.

About the preservation: who knows what’s coming ahead of us. We couldn’t imagine any of this in the ’80s! When I first heard about digital photography, I actually said, “That’s when I put away my cameras, there’s no way I am going to learn how to do it.” It seemed, at the beginning, completely beyond anything that I knew, “I am going to retire!” Then, I remember this moment, I was in Chinatown, I saw this old woman probably younger than me now—a little old Chinese woman—and she had a digital camera and I’m looking at her and thinking, “If she can do it, I bet you I can learn how to do it.” But it wasn’t an easy transition for me. I am not a techy person. I even learned how to use Instagram!

In the future, all digital recording devices will have wifi and you will be immediately able to send it to your perfectly organized cloud where it will be archived automatically. For the preservation, you need the correct storage and archiving. We even need a universal archiving and retrieval system, so that if I die tomorrow, you will be able to go into those files and find whatever you are looking for. Otherwise what are we doing in here?

***

Follow Martha Cooper on Instagram at @marthacoopergram and on her website nycitysnaps.com. I have to give thanks for the help of Davide Rossillo of Memorie Urbane and Antonella Bartoli on this article, who is known for stealing her boyfriend’s The Hundreds sweaters. Next trip will for sure be Berlin in 2016.