The Hundreds X The Karate Kid releases April 27, 2018.

Nestled snugly on America’s credenza are trinkets of culture that warmly remind us that we love ourselves. We have shiny plates of muscle cars, saucers of Super Bowl victories, polished pop-culture dance crazes, and various iterations of Madonna. When company comes over, we awe them with our trophies of Will Smith.

And recently when we’re in the mood—which seems to be always—we rummage through the photo-albums of our collective conscience, taking in the spectacle of our own cinema. These slides like cultural time-capsules for the future people we grew up to be. There below us, a dulcet veneer of stories of mystery, love, calamity, and perseverance, all in three acts. Thumbing through the album finds preserved pieces of what we wore and listened to. Arrangements of storytelling there to smooth out the corners of our societal aims. The ethos of the American cinematic experience is clear: We are regular Joes. We are adventurous. We are triumphant.

Page after page of movies nourish our memories, splashing dopamine hits of nostalgia, while providing an opportunity to remember the seminal touchstones of times before.

We were thinking The Karate Kid.

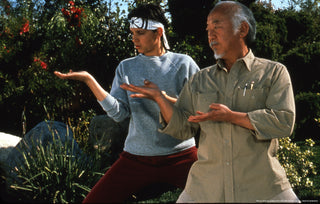

If your name is Daniel, the reason that you’ve been called “Daniel-san” at every job you’ve had, is because of The Karate Kid. Your immaculate fence-painting techniques—The Karate Kid. Hands slowly raised like wings of war. Then that flying kick. That’s The Karate Kid.

Originally released in 1984, The Karate Kid is a cinematic national monument. It was born into a particularly unique orbit of American landscape of ‘the ’80s,’ in which the future felt just around the corner, California was fetishized as a land of one parcel of beach per citizen, and cool seemed measurable.

The ‘80s were the rail station where the martial-arts fads of the ‘60s and ‘70s ended up. On the older side of 1984, the cinematic protagonists were both gun-wielding and Judo-chopping. Martial-arts flicks were slinking off the path of one hero’s righteous journey through a madman’s palace, onto more ultra-violent hard-boiled, gun in one hand, deadly weapon as other hand flicks. The ‘60s watched Kung-Fu’s novelty while the ‘70s exploited Karate’s badassery. And by the ‘80s, all cinematic henchmen were trained ninjas.

But the unique asterisk on the timeline of ‘80s martial-arts flicks is the composition of The Karate Kid. It seemed to be Hollywood’s gamble to see if they could string the popularity of martial-arts into fun for the whole family. And it worked.

The body in the director’s chair was John G. Avildsen, who was at the helm of preceding iconic American flick, Rocky. Avildsen transposed similar underdog themes onto a new landscape in sunny California, supplanting a wooden deck for the meatpacking plant. The skeleton of the re-packaged Rocky-in-California is successful not solely because we align ourselves with the protagonist, but we are thrust into a refreshing master-student relationship that is genuinely charming and supported by witty quips that land, and a seemingly palpable rapport between Miyagi and Daniel. When Daniel-san beats Mr. Miyagi to catching a fly with chopsticks, Miyagi remarks, “Man who catches fly with chopsticks, accomplish anything,” before finishing with, “but first accomplish paint fence.”

The public swallowed this movie whole. At the time of its release, Roger Ebert gave it four out of four stars, which in ‘80s parlance is like going to Disneyland with Michael Jackson and Bubbles.

While the story is somewhat from tracing-paper, it’s the cast that does the heavy lifting. Elisabeth Shue as Ali is the perfect California blonde from the right side of the tracks with that toothy smile, and William Zabka as Johnny is the perfect evil blonde of the Cobra Kai dojo (Draco Malfoy before Draco Malfoy), Randee Heller is perfect as Daniel’s mom or “Ma,” winning the scene in which she and her son embarrassingly roll-start their car from second gear. And of course, there’s the karate kid himself, played by Ralph Macchio. The young Macchio plays well to the camera with his witty quips, and his boyish “baby browns” are easy on the eyes. Macchio’s soft facial features and muted masculinity lend perfectly to an appeal to both boys and girls. He’s a protagonist you can transpose yourself upon as you montage your way to a crane-kick finish. What is more American than that?

And what is more ‘80s than this movie?

The Karate Kid’s charm during its contemporary run paired America’s fervor for fish-out-water underdogs with its favorite fighting style. But an eye backward finds a film that delights our retrophilic live wire. The late Gen-Xers and early Millennials batch that crushed Stranger Things in a single sitting can find everything ‘80s they’ve ever dreamed of in The Karate Kid. It’s decorated with an orange-ish California Valley feel, dotted with colorful dirt bikes, beach bonfires, boomboxes, boombox fights, feathered hair (and mullets), cut-off tees, arcades, and long-swooshed Nikes.

We are the rooters for the doers, and the doers of the unrealistic.

When Daniel (and his mom) pick up Ali at her expansive Encino abode, her parents send her off in trademark red, white, and blue FILA track suits, which at the time, was thee fashion symbol of affluence. Daniel-san dons a raglan tee, beltless dad-jeans, and dirty Nike Cortez sneaks. Our villains at the over-the-top militant Cobra Kai dojo wear cut-off sleeveless karate gi—a fashion gesture radical enough to visually suggest that these are the bad guys. It is a marker of a simpler time without the internet, when you had to have the directions to the party before you left the house.

Moreover, the construction of the film stimulates a strong ‘we grew up on this’-sensibility. And that sensibility clambors for the good old days of cheesy exposition music. I had a hearty smile at “(Bop Bop) on the Beach”—the song that plays while Daniel and the boys soccer around on the beach, really setting the California vibe for the backdrop of the movie. Then in a comical fade to night on what’s presumably the same beach, the crew roasts hot dogs over an open flame, while girl-to-win, Ali and her gang sit just some distance away listening to their boombox, with their own bonfire. The song that plays is a synth-lead downtempo crooner birthed from a Patrick Nagel painting, “It Takes Two (To Tango).” It sounds as delightfully wholesome as the title suggests. But this is just the beginning.

The real delightful audio assemblages come with a tune forged in the fire of all movie montages: “The Moment of Truth” by Survivor. Its inspirational spirit, and uptempo hard synth pulses are only outdone by its lyrics of courage. “Once in your life, you make a choice, ready to risk it all/ Deep in your soul, you hear the voice, answering to the call.” Eat your heart out, “Eye of the Tiger.”

And lastly, no tune from the film is more ‘80s than Joe Esposito’s triumphant to a tickle, “You’re the Best.” Legend has it, if you can find a phone booth, and walk into it wearing tube-socks, listening to that song on a walkman, you emerge at a cast party with the Brat Pack.

Even if The Karate Kid has aged from our vantage now, it works. Its melting pot of amiable characters, martial-arts, and small-fry ascendency spawned a new 2018 television series following a now-grown up Johnny Lawrence—Cobra Kai. The spirit of it is truly American in so many senses that it proves a cultural touchstone for so many people. We like our heroes to beat the bully and to get the girl. We like to believe that with a little bit of charm, a series of lessons with an old guy, and a quick splicing of feats of determination, we can montage our way from novice to expert in one quick summer. We are the rooters for the doers, and the doers of the unrealistic. That is America. And we love this movie because it reflects what we hope to be, even if it does so cartoonishly. We’re optimistic somewhere deep down in there, and when we lived it the first time, it was so, and when we look back at it now, we steal a little optimism from our perch here.

Wax on. Wax off.

***