If you’ve been sleeping on TheHundreds.com, IMO is a list series that tackles BEST OFs with the indubitable authority of, well, our own opinion.

Regardless of the genre of film you plan on seeing at the theater or watching on the behemoth flat-screen at your home, one thing is for certain when it comes to the movie-watching experience: there are expectations. People want to be moved. They want to be scared. There are instances when they want to be challenged and there are times when all that is required is enjoyment. With the recent success of David Fincher’s newest film, Gone Girl, which is based of Gillian Flynn’s best seller of the same name, it’s hard to ignore that the film unfolds in a less than traditional manner – completely abandoning certain inherent storytelling methods in favor of unreliable narration and a shocking midpoint turn that is usually saved for the third act. While there’s always room for the classic love story or action-packed thrill ride, it’s always nice when satisfaction stems from something you hadn’t expected. Here are a few films that toss out the rulebook.

::

MEMENTO

Perhaps the contemporary gold standard for disregard for linear structure, Christopher Nolan’s 2001 film was a reminder to audiences that if a storyteller truly did his job correctly, the elements in a film were but a small cross-section of a vast universe where beginnings and endings are merely chapters as opposed to bookends. A follow up to his debut feature, The Following, which also employed a non-linear format – and based off a short story written by his brother Jonathan called “Memento Mori” – the film unfolds in 22 scenes with backwards elements in color and things that push the story backwards presented in black-and-white.

While some will point to the format as a trick or gimmick, Nolan argued that it served to put the audience in the shoes of a main character who was dealing with anterograde amnesia. In speaking with Indiewire he said, “It’s like we try to put you in his head and that’s why the story is told backwards, because it denies the information that he’s denying.”

::

THE USUAL SUSPECTS

Much like the aforementioned Gone Girl, filmmaker Bryan Singer’s 1995 film The Usual Suspects relies heavily on the notion of the “unreliable narrator.” For anyone who has picked up a screenwriting book or attempted to dissect why a movie works so well, it’s because in the antagonist’s mind, he is actually the hero in the story. What makes a villain evil as opposed to cartoonish? They believe that what they’re doing is the correct/necessary thing. The Usual Suspects plays with the idea that the audience can only form an opinion on the events of a story based on who is telling it and what they choose to enhance and what they choose to leave out.

::

RASHOMON

Comprised of four different retellings of the murder of a samurai – as told by a notorious bandit, the samurai’s wife, the woodcutter, and the samurai himself – Rashomon explored the nature of truth and testimony and laid the foundation for other films like Fight Club, American Psycho, Taxi Driver, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Citizen Kane, The Informant!, Atonement and more.

::

500 DAYS OF SUMMER

Based on the title of the film alone, we already come to expect that there’s a ticking time bomb associated with the budding romance and ultimate dissolution of love between Tom and Summer. As a means to play with our expectations, the days associated with their courtship play out in a non-linear fashion – allowing the audience to get payoffs for fleeting glances and sourpuss exchanges in reverse order – abandoning the notion that the climax in a story must come after the set-up.

::

SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE

Slumdog Millionaire begins with a series of questions – both literally and figuratively – as the thematic premise of the film is broached: did Jamal cheat, get lucky, or is he a genius? Filmmakers are always looking for inventive ways to “hide” backstory without making their creation feel exposition-heavy, but it’s Danny Boyle’s choice to use a game show and the attached questions as a means to look back which proved to be a particularly natural marriage between the past and present.

::

ADAPTATION

The collaboration between Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman that resulted in Adaptation can best be described as a “film about trying to make a movie.” While notable films like Argo and Sunset Boulevard tackled a similar notion, the self-awareness associated with the films – and the meta nature of the plot’s construction – made it felt like a completely new premise despite it being a familiar Hollywood trope.

As history goes, Charlie Kaufman was actually hired by Columbia Pictures to adapt Susan Orelean’s novel, The Orchid Thief, back in 1997, and ran into a case of writer’s block (the exact premise of Adaptation). Unable to get a grip on the story, he decided to focus on his own process with a few fictional elements sprinkled in. By the end of the film, viewers have been given performances of real people playing themselves, actors playing real people, and complete fabrications.

::

CITY OF GOD

Employing a similar narrative construction as something Quentin Tarantino might come up with, City of God used split narratives in a shared universe as a means to ultimately pay off what life was like inside a Brazilian favela. With the individual stories of The Tender Trio, Little Ze, and Knockout Ned, the direction not only plays with the notion of perspective, but also of when events took place in relation to the multi-layered storyline.

::

OLDBOY

Not only does Oldboy employ a vast jump in time – from Oh Dae-su’s imprisonment in 1988 to his release 15 years later in 2003 – but it also plays with the idea of who is truly the protagonist and whose personal revenge story should we be rooting for? Ultimately, it’s for the viewer to decide, but as the narrative plays out, slowly our feelings of sadness for Dae-su morph into empathy for his captor, Lee Woo-jin.

::

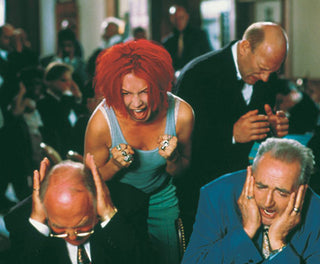

RUN LOLA RUN

If imitation is indeed the truest form of flattery, then Run Lola Run owes a lot of it’s plotting and pacing to the 1987 Polish film Blind Chance. Featuring three different storylines about a man running to catch a train – and the various outcomes he faces depending on how he deals with various obstacles – the more contemporary film starring Franka Potente injects the ticking time bomb of twenty-minutes to secure 100,000 Deutsche Marks or her boyfriend will be killed. Featuring three different “runs” as a way to solve the problem, we come to understand that hidden amongst the high-octane action is a critique on how arbitrary things influence our lives and how succumbing to one’s fate is ultimately a small death unto itself.

::

PULP FICTION

Quentin Tarantino has been quoted in the past as saying, “novelists have always had complete freedom to pretty much tell their story any way they saw fit. And that’s what I’m trying to do.” Essentially, Taratino as writer/director/crazy person is free to make not only the movies he wants, but tell the stories in whatever way he sees fit. If that means telling them in chapters, he’s done that. If that means rewriting history, he’s done that as well. Sure, Reservoir Dogs and True Romance were great movies, but with Pulp Fiction, it all seemed to converge in a single package of snappy dialogue, moral ambiguity, and inventive structure.