David Umemoto, at his core, is a sculptor. Having spent some time in Asia working in an office, he’s attempting to relearn how to work with his hands—something that he yearned for at his 9-to-5 desk job as an architect. Designing government buildings and schools weren’t creatively fulfilling for him, so he found a way to take his interest in architecture, art, and deconstruction to create unique, modular concrete sculptures. His approach is self-described as “rigorous,” with each sculpture comprising of modular sections that can be reorganized to create new forms. I visited David’s studio to see his work in person.

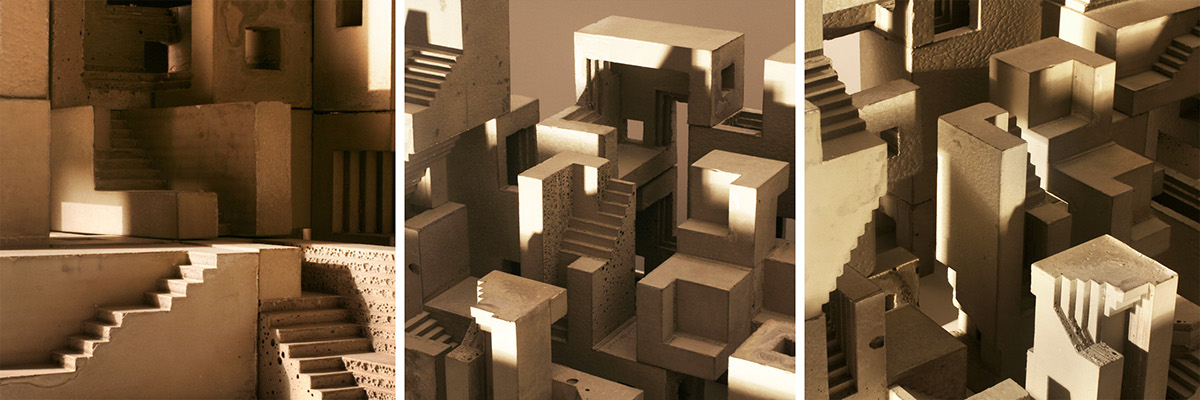

“Foundation”

“Foundation” with its modular sections reorganized

JOHNNY F. KIM: [I feel like I can describe] your art form as raw. Knowing your background in architecture and computer graphics, why have you chosen to create something physical versus digital?

David Umemoto: When I started developing my ideas on my work with concrete, I was in the computer graphics field and doing a lot of rendering for architecture projects. So most of my work was digital. But, I personally thought that the way you design digitally was limited, and to most people it was not a real issue, so I tried to figure out a way to make architecture designs that would live beyond a digital platform and also be able to present it. For example, instead of making renders, I would take photos of my physical models, since everything I made is right there in front of you and you can touch it and play around with it. That also triggered an idea about making it interactive, like my blocks or tiles are in some way like a language, since you can move them around and make new art pieces out of them. They can all be modified.

Also, since we are talking about digital versus physical: When you create digital projects, all of your life’s work can be stored in one file and with a click of the mouse you can erase it and forget about it. What I like about my work is that it can live forever and you can’t really ignore it since it’s there physically; I have no choice [but] to store it somewhere or physically destroy it.

Detail from “Soma Cube City i“

Your work is created in a smaller scale. What are some pros and cons of making it small versus a larger scale?

Well, a great advantage is that there is a lot of room for error and more creativity since it is a small scale and you are not really committing yourself to anything. You can always start over. The reason I say this is that if I were making, for example, a large building—if you designed it and your project is finalized, then it gets built and you see the building there. And if there is something you don’t like, well, you cannot really change it or decide to scrap it and start over. It’s there, it’s big, and it will be there for 100 years at least. And people won’t really pay attention to certain details, they will say, “What is that ugly arch or stairs,” etc., and not really consider the other factors—like, I had to design it that way since there was a tunnel or a pipeline. So it is a bit unfair for architects working on large scale projects.

But there are also disadvantages of working on a small scale, right?

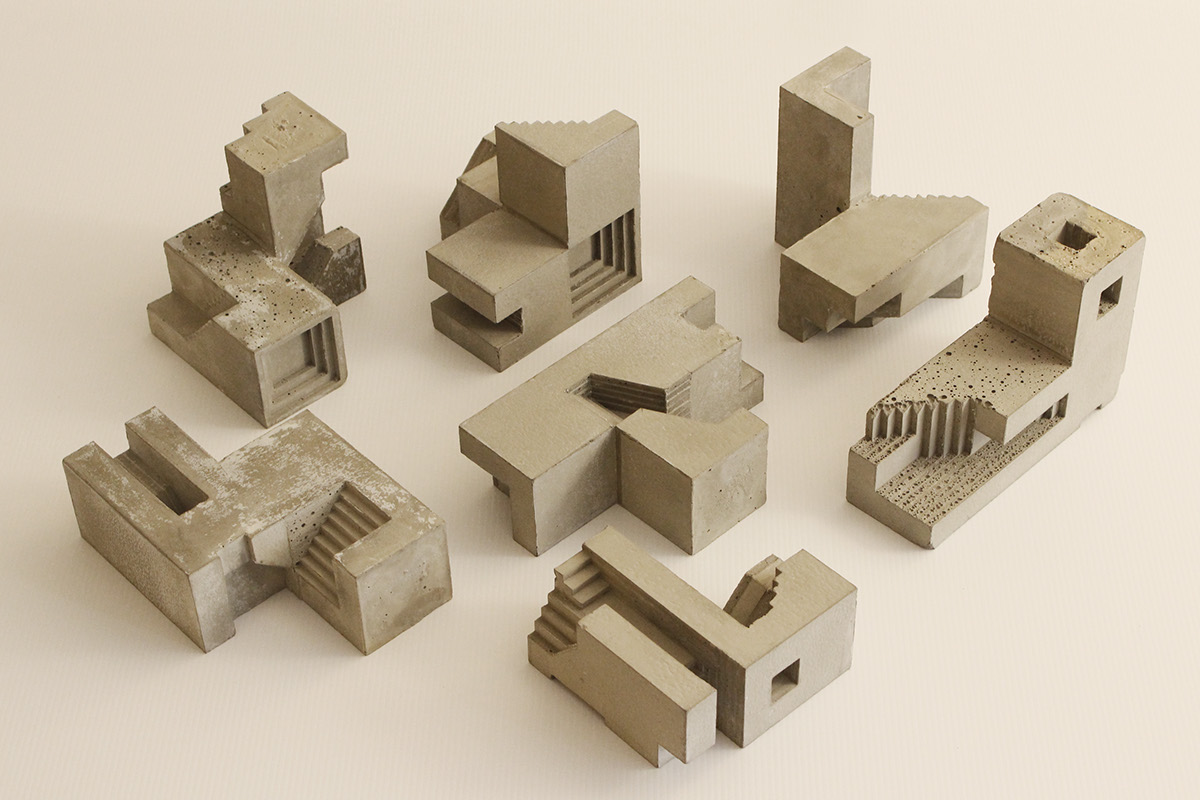

I don’t think it is a real disadvantage, but your detailed mistakes can be more apparent. Like an air bubble is more in your face on a small scale, and on a large scale it will look like dust. I also think that my work can be seen as small scale and large scale since it is modular. I can take all my blocks and put them together to create a bigger work. So it is advantageous in the end… Actually, I currently am in the process of doing that. I can’t really show you anything since it is in the process of getting created now.

David Umemoto in his studio.

Where do your designs live after its creation? Do you ever think that one day future generations that discover your work can interpret it as being an ancient art form?

Nope. But, I do get that comment about my art being ancient. So if it’s ancient now, it will be ancient in 50 years or forever. So that is good to know.

How does the geometry of your designs represent potentially universal connectivity and order? What does that mean for you?

At the moment, I am not really trying to be too deep in the meaning of my art. I just want to think less and not worry about the why, what, where, and just do it. My perception always evolves… [it] can be confusing about what I say at a certain time[s] and be a total different meaning at another time. So, I just want to think less and just create for now.

In the past, you have described your work as being represented as the theory of “order and chaos.” Can you elaborate on that?

Sometimes my work, from far away, it can look like chaos. Like the earth for example, when you look at it, it’s just a blue planet—it looks chaotic. But when you zoom in, you see more in depth, you see the clouds—zoom some more in, you see the canyons. Or the reverse is you zoom out you see the universe. So by zooming in or out, you see some sort of order that works together. Everything is organized together, but also it can work on their own. So that’s what I meant.

“Soma Cube iii” deconstructed.

How have you managed to stay unique in your niche of work?

I am not really sure how it happened or how I can explain it, and my art might not be niche in the near future. There’s probably a bunch of artists doing similar work like me that no one knows about. But, I have had my work described as being part of the “brutalist” movement of the ’60s. At first, I took it a bit negatively, since some of the work of that movement is very cold or somewhat boring—but some of it is beautiful as well. Since my work is mainly made out of concrete material, people sort of identify that material to that movement. If I did it in wood, it is the same shapes and geometry, but it would not be “brutalism.”

My work can also look like buildings. People also associate the details I chose to put in my blocks to look like buildings. What they don’t know is that, sometimes, I decide to put a certain detail—for example—in a stair shape. The reason I put it there is that I just wanted an angle. It just happened to be a 45 degree angle in low res so it looks like steps, but it was meant to be an angle. So they immediately associate it to, again, a building. So the perception of my work does differ from one person to another—some say brutalist, some say buildings, and some say Aztec even. I know why they say that, but those details were never meant to represent that—it was just a low-res angle. But yeah, I am aware of what I create and do understand why they would think that.

***

davidumemoto.com. Follow David on Instagram @david_umemoto.