The “high-five” as we know it doesn’t seem like something that had to be invented. We’re at a time and place in advancement where innovations promise things that seem outer-worldly—like driverless cars and shoes that will lace themselves. Those are inventions; the high-five is a tactile expression that hits with more impact than a yellow emoji and reminds us that every once in a while, it’s good to rip ourselves away from our reliance on technology and go celebrate something IRL.

Believe it or not, the high-five not only has roots in sporting culture—where it is so widely used—but the digit-to-digit slap has its origins right here in Los Angeles.

The year was 1977. It was business as usual in the country, although there were several notable events that registered like tiny blips at the time—most notably Apple Computer incorporating, George H. W. Bush ending his term as 11th director of CIA, and Rocky taking home Best Picture at the 49th Academy Awards.

From a more regional sporting perspective, the Los Angeles Dodgers were also looking to become the first team to ever have four different players all reach the 30 home run plateau in a season. At the time—prior to steroids pervasiveness in baseball—30 home runs meant you were a certifiable slugger. Even in today’s context, the murderer’s row of Dusty Baker, Steve Garvey, Reggie Smith, and Ron Cey would have outpaced two big league clubs in home runs all by themselves.

But a fifth man would figure into the invention of the high-five as well; a rookie, Glenn Burke.

Glenn Burke

Photo: competenetwork.com

Burke himself grew up in Berkeley, California where he starred in both baseball and basketball. As a minor league prospect, he hit over .300 in five seasons and had tremendous range in centerfield—causing Dodgers scout Jim Giliams to refer to him as, “the next Willie Mays.” However, of the four men chasing the 30 home run record as teammates, three of them played in the outfield, meaning Burke was a man without an opportunity or a position.

“He would have been real good if he had the opportunity,” Dusty Baker said. “I mean, Glenn could play, man.”

Although he was scarcely used during the 1977 season—appearing in half of the games and only getting 169 plate appearances—it didn’t affect Burke’s willingness to embrace and champion his teammates run at baseball immortality.

While lesser players would have crumbled from the lack of usage alone, Burke was also contending with the fact that he was out to some in the clubhouse as a gay man, which is something that remains a taboo subject even today.

“They knew the way parents know their 16-year-old is drinking beer but don’t say anything until the bottles are rolling across the floor of the family car,” explained the 1982 Inside Sports profile about Burke. “As long as Burke’s homosexuality was not official, no one felt compelled to react.”

Like many sports narratives, the record came down to the very last game of the season. Steve Garvey, Reggie Smith, and Ron Cey had each already reached the 30 home run milestone in previous games—leaving Dusty Baker with three at-bats to write all of their names into the hallowed MLB record book.

Steve Garvey, Reggie Smith, Ron Crey, and Dusty Baker // Photo: pinterest.com

Squaring off against the Houston Astros in front of 46,000 roaring fans who rose to their feet in Chavez Ravine each time Baker stepped into the batter’s box, the slugger struck out and singled in his first two plate appearances.

As fans are known to do, they began to grow restless at the Dodgers’ lackluster play—recording only three hits and down two runs through five innings—and worried that Dusty Baker was only going to get one more shot at the record. As Baker proved, he only needed one more shot.

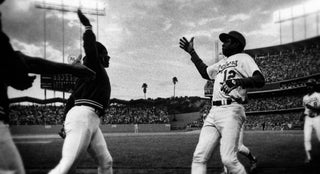

According to MLB.com, “In the sixth inning, in what would be his final at-bat of the season, Baker lifted a 1-2 James Rodney Richard delivery over the wall in left. Burke, in the on-deck circle, met his teammate at home plate with that right arm extended, up high. Baker—”Dr. Scald” to teammates—hammered it with his right hand.”

As The Washington Post noted, “In photos, Baker leans backward, his own right arm crooked awkwardly up as if he isn’t sure what’s coming. Then the two slapped their hands together.”

Photo: fastcompany.com

Whether the high-five had happened before or not, no one on the Dodgers had ever done it before. It was celebration in its rawest form.

As if the fairy tale ending wasn’t perfect enough, Burke dug in for his at-bat and cranked his very first homer of the season. And wouldn’t you know it, Baker was there to greet Burke with a high-five of his own.

“Glenn loved that the high-five caught on like it did,” Baker said. “He was the life of every party. Nobody could dance like Glenn. He was always doing his poetry off the streets of Berkeley, on the bus, and the team plane. Glenn kept everybody loose and laughing. You need that kind of guy on your team in a long season.”

Two months into the next season, Dodgers management shipped Glenn Burke to the Oakland A’s for Billy North.

“I was talking with our trainer, Bill Buhler,” Dusty Baker remembers. “I said, ‘Bill, why’d they trade Glenn? He was one of our top prospects,’ He said, ‘They don’t want any gays on the team.’ I said, ‘The organization knows?’ He said, ‘Everybody knows.’”

Burke’s time in Oakland saw him get the opportunity to play much more than he ever did in Los Angeles. But the combination of his teammates frosty reception due to his sexuality, and a litany of injuries like a pinched nerve in his neck and bad knees, forced Burke out of baseball two years later.

Glenn Burke died from AIDS complications in 1995. His impact on the game of baseball—both fun and heartbreaking—will and shouldn’t ever be forgotten.

***