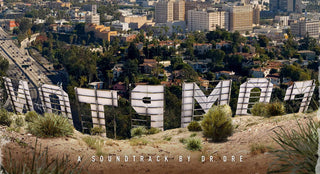

Dr. Dre said he ultimately shelved Detox because he believed he didn’t do a good enough job. He simply wasn’t proud of the music he was making. What we as fans netted in terms of music were leaks that were disjointed tracks by rappers with promise we’d never heard of, nor would hear from again (ehem, Bishop Lamont). Nowadays it appears that the doctor wants to disown its very mention like a bastard child with medical bills. But he’s the d-o-c, right? It’s been sixteen years since Chronic 2001 and the one-time harbinger of West Coast glory has gathered his white-coat, stethoscope, and clipboard for a return to surgery with Compton: A Soundtrack by Dr. Dre.

The prognosis? It’s just aight. Very medium. Decent. Coo. Good enough, I guess.

Which, by most comparative standards for Dr. Dre, is pretty underwhelming. Now, one is hard pressed to say they’re plugging through Dre’s catalogue to find his hardest hitting verses, or most clever exploits as a wordsmith, because, lord knows, you don’t listen to Dr. Dre because he’s the best rapper in examination room. You’re listening for who’s been invited to the party, and to which phenomenal instrumentals they appear on. An experience with Dr. Dre is about the production of beats, and those artists that are featured upon those beats. So when Kendrick Lamar delivers an exceptional verse on “Deep Water,” one could argue that it’s par for the course on our collective expectations. Dr. Dre—the artist—pivoted his way through rapping + producing, to producing + rapping. Think of it in terms of Instagram once being a social app that allowed you to check in at whiskey bars. The natural career pivot has shifted the focus off of Dre as a rapper, which he tries to do in earnest on Compton.

It comes off forced and shaky.

“Talking To My Diary” is as melodramatic as it sounds, and that very sound is hampered further by Dre’s forced sincerity over a track that was most likely ghost-written. He raps “I used to be a starving artist, so I would never starve an artist.” Isn’t that a sweet notion self-martyrdom? But it ultimately feels like a half-sincerity coming from the dude who’s made more money off of headphones in the last five years than his entire catalogue combined, and who once famously claimed file-sharing was taking food out of his kids’ mouths. (I didn’t know kids ate hotels).

This is not to suggest that Dre is not from where he says he’s from, and that his rise to the top wasn’t the product of tenacity and hard-work. As I’m sure the Straight Outta Compton biopic will demonstrate, Dr. Dre didn’t start at zero, he started far below that: a lack of the necessary resources to crack the industry; It had to be done with only the support of friends, with talent as the vessel, and the focussed chutzpah to overcome adversity stacked on adversity.

Remember, this album is a soundtrack to a movie about the rise of N.W.A.—a group that had arguably the single most influential impact on hip-hop today. It was the combination of the consciousness of Public Enemy, paired with the grit of all out anti-establishment rejection of social niceties, birthing Gansta-Rap. The nexus of where struggle meets cool, where thug-life meets lyrical storytelling. Groundbreaking is groundbreaking. It can’t be forgotten that in a soundtrack of a flick about that actual rise, tracks may aim to be thematically more topical, as to be cohesive to this story’s narrative.

Thus, this album cannot be any of the other Chronics. It’s got to be more political and less about blunts and hoes and housewifery.

The intro track gives its political tilt offering a brief and depressing summation of the history of the Compton Dre rose from. “All In a Day’s Work” offers hearty candor about the grind, and it’s buyable. The track “Animals” provide a great showing from the multi-talented Anderson .Paak who offers a solemn, “Please don’t come around these parts/ And tell us that we’re all bunch of animals/ The only time you wanna turn the cameras on/ Is when we fuckin’ shit up.” With sincere lyrics, and a distinctly west-coast melody driven beat, it is reminiscent of that auburn California sunset that Dr. Dre can produce with his music. Unfortunately, the gravitas and chill of the song is hijacked by a wholly superfluous DJ Premier shot out as the beat closes. Its that spray of cheap perfume when you’ve already lathered up with scented body lotion.

And this is one of the most objectionable things about Compton. It’s not that it’s not west-coast enough, it’s not that it’s not party enough, or single-laden, but that it’s entirely too busy. Kendrick’s amazing verse notwithstanding, “Deep Water” is an all out muddy and crowded track in every way possible—overproduced. Dre’s own verse is so top-loaded with vocal layering and effects it sounds like a dub step producer put Dre’s lyrics onto midi pads and tried to tap out his verse. It’s sonically clunky and turbulent until rescued by Kendrick, who even then is barely able to save it. For most of the album’s tracks, the production—purely from a beats (no headphones pun intended) perspective—could use some of that Kanye austerity—a sound Dre helped popularize! If you have a beat that is so strong before artists even have a chance to rap on it, don’t clutter it. Allow it to sing for itself with a nice intro, breakdown, or playout. This is absent on the whole from Compton.

There are some shining moments that are undeniable on this soundtrack, however. The first song “Talk About It” is easily a trunk-banger that will sound good on the block as Dre exclaims a very singalong moment of “I just bought Cali-fonia!” It undeniably turns up to 11 and King Mez’s autotune seems cohesive with the times. “For The Love of Money” offers an underused Jill Scott feature, but is saved by it’s nod to Easy-E, banging back beat, and voluminous bassline. The beat is trounced by a chopper of a verse by up and comer Jon Connor who lyrically rides the hard snare. Dude’s verse is mean, and Dre’s attempt is better than decent. “Loose Cannons” provides a touch of Xzibit, which is always better to hear him over a Dre beat, than to see him as a meme online.

Then, of course there’s the Eminem feature, “Medicine Man” which is so thoroughly exemplary of his fire that writing about it simply will not do it justice. Dre switches up the beat in the middle of his bars and all listeners will be in for a sheer rap-gasm. Not to mention, it has my favorite singing feature where Candice Pillay tells “Doctor’s orders/Go fuck yourself/ Take two of these in the morning, overdose and kill yourself…Doctor’s orders.” Send that track to friends and insert the appropriate emojis.

So, Compton: A Soundtrack by Dr. Dre is decent. The world has been starved of Dr. Dre for so long, that perhaps anything that he’d put out next could be crushed by the hype surrounding it. It’s possible that this album suffers that fate as Dr. Dre-the legend chokes out Dr. Dre-the music. It is undoubtedly suffering as being the first full-length offering since the older-brother Chronic albums left their marks in our headphones and at our parties. A friend of mine ruminated that since this album isn’t as initially approachable as Chronic 2001, it’s going to take a very attentive listen, as many hip-hop heads had to offer to Kendrick’s To Pimp a Butterfly, which has grown on the once skeptical. But that comparison isn’t equal. There are simply things about Compton that cannot be corrected: the order of the tracks (most of the good ones are at the end of the album!); the cluttered arrangements; the so-so features; the forced sincerity. We hoped for an opus and simply got an offering in the form of a soundtrack. But nonetheless, it’s an offering worth taking.