When I was 11 years old, I found a Feelies tape in the dollar bin at The Wherehouse music. This was not a cool independent record store. It was part of a chain that was furthermore part of a much larger corporation who was once sued for “CD price fixing,” but it was three blocks from my house and I had no driver’s license. What I did have was allowance money burning in my pocket, budding breasts, and an ocean of angst salting my whole existence. If books were my splintered raft, music was the light reflecting off of a far away boat. Pre-teen me would have written this bad metaphor into a worse poem.

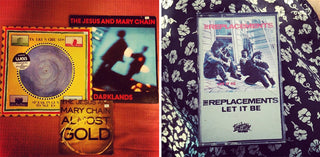

I bought the Feelies tape because the cover was an arresting shade of blue and it looked interesting and because that was something you did back then—you took risks and it was thrilling to buy a record just because the band had a cool name or weird cover art. This was 1993 and I think the internet existed but there was no time to go home and navigate the labyrinth of MS-DOS and dial-up squawks to get to information, you just committed. There was danger to it, and when it paid off, it paid off big—in this case in the form my first taste of jangly, offbeat post-punk, a record I still listen to 25 years later.

In high school, I started frequenting the South Bay’s few excellent indie shops, like Go Boy and Off Beat. I got really into bootlegs and zines and a local punk band called Deviates, which I listened to on repeat in private (along with Blink-182, and for different reasons, Dave Matthews Band) when my parents moved me away from Torrance and to Singapore where the ocean developed a riptide. I cried a lot and pretended to like group sports. I watched Empire Records and decided that I wanted to work in a record store when I grew up.

Yasi at fourteen.

In college, I went into Morninglory Music in Isla Vista and dropped of my resume and a meticulously crafted mixtape (Feelies were on there) as my application, then proceeded to come in every single day after that to ask the manager, Dave, if a job had opened up yet. A job never opened up but Dave hired me anyway because he could no longer stand my cheerily beseeching visits. I didn’t grow up but to this day, it was the best job I’ve ever held. Will, a grad student who wore thick-rimmed black glasses and a variety of striped polo shirts and who always smelled faintly of onions, told me about the White Stripes and made me mixes with Silver Jews songs on them. I got deeply (some might say ruefully) into underground hip-hop, and I sat on a stool eating tuna sandwiches and drinking Diet Coke and listening to new interesting music every single day. Steve Aoki would come in and drop off flyers for the hardcore shows he threw at his house. I asked a guy out there once, and he turned out to be a Juggalo of sorts. I lost my virginity to him and then he went to jail.

Morninglory closed and I lost my dream job around the same time I started writing, mostly embarrassing music “journalism” for the Santa Barbara Independent, along with a movie review of the film Down With Love for which I received one piece of hate mail. It stated: “I don’t think you know what love is.” After college, I moved to San Francisco and interned at XLR8R magazine. I lived in a house with four tech bros from upstate NY on Fillmore Street next to an abandoned hotel-turned-crack den. I wore a lot of black. I went into Amoeba Music, the one on Haight Street, for the first time, and decided I still wanted to work at a record store when I grew up.

The Amoeba in San Francisco is vast and electric. There were always interesting people stalking its aisles with armfuls of vinyl. My friend Hether once quite literally bumped into Jimmy Page there while digging through the dollar bin. He told her to “calm down.” In 2003, I wasn’t very interesting and I only ever had one record in my hand. It was all I could afford because despite my career aspirations, Amoeba would not hire me. I went there almost every day anyway, to watch people I was too afraid to talk to and to keep tabs on the employee I was sure I was in love with but was also too afraid to talk to, but mostly to just lean on its energetic buoy when I needed a rest.

That’s what they are, independent record stores and bookstores: buoys for the drowning. You can be around these thousands of records, all this untold promise, lovingly pick them up and put them down for hours. You can linger, you can leer. An employee who is probably in a noise band will advise you on their favorite Pavement record or let you touch a Crass Shaved Women 7 inch you can’t afford. They will give you a flyer for their show (they go on at 1 a.m.). The whole place exudes promise. There are Jimmy Pages around every corner, perfect songs in every bin.

My dreams don’t really include jobs anymore, and Steve Aoki crowd surfs on mattresses to electronic dance music now. My own ocean has somewhat calmed, but it’s still just as salty below the surface, and I still need buoys, and the small thrills of the hunt, the potential for random discovery. Amoeba Music is one the last bastions of the spirit of that parallel dimension I discovered when I was 11, unlocked by that bet on a blue Feelies tape. In Hollywood, its neon light is still the brightest, and last I checked, they still have a dollar bin, if you’re picking up what I’m putting down.

***

The Hundreds X Amoeba Records drops Thursday, June 7, 2018.