When you think of boxing movies, Rocky is invariably the first that comes to mind. The iconic film was an immediate financial and critical hit when it debuted in November of 1976 and it went on win numerous accolades including Best Director and Picture at the following year’s Oscars, with Sylvester Stallone also nominated simultaneously for Best Actor and Original Screenplay, an extra-rare accomplishment matched only by Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles.

Beyond that, and perhaps more importantly, this is a sports movie with an almost unparalleled cultural impact. It’s not at all hyperbolic to state that Rocky pretty much established the prestige sports film genre that eventually led to include other lauded classics such as Raging Bull, The Wrestler, and, more recently, 2015’s Rocky reboot/sequel, Creed. To this day, both Rocky superfans and those who’ve never even watched the film can quote lines from the movie, sing “Eye of the Tiger” word-for-word, and uncontrollably fist pump at the top of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 72 stone stairs.

Even the sartorial choices of the film’s titular character have seeped into society, with the boxer’s simplistic grey sweats aesthetic coming back in vogue in the wake of the sleek and hyper-engineered technical workout gear that flourished in the athleisure era. With our own The Hundreds X Rocky collaboration about to drop, we thought we’d share the mythos and legendary origin stories behind this seminal work of art.

***

Similar to its own protagonist’s, the story of the Rocky going from idea to script to beloved cinema classic is one of a hardscrabble underdog rising from nothing to something through difficult choices, hard work, and sheer willpower.

To say that Sylvester Stallone had a rough life before Rocky would be a bit of an understatement. From his earliest moments, life was all too eager to slap Sly around a bit. Complications during his birth resulted in the forceps used to deliver him severing a nerve, giving him a partially paralyzed face and his trademark slurred speech.

Bullied for these traits throughout his childhood years growing up in the impoverished and crime-laden neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, Stallone floundered his way through school with poor grades and frequent suspensions for fights resulting from his behavioral issues. But home was no sanctuary either. The kid bounced between relatives’ homes to avoid his parent’s constant fighting.

Stallone’s bad luck hadn’t abated by young-adulthood. After an eviction left Stallone homeless and sleeping in the Port Authority bus station for three weeks, he accepted a $200 gig in a soft-core porno out of desperation. The desire to be cast in less seedy roles now beckoning him, Stallone threw himself into the pursuit of an acting career, only to face non-stop rejection from casting directors. Realizing he’d have to devise his own roles if he ever wanted to land one, Stallone turned to screenwriting, teaching himself the process from scratch. But even though he’d found the medium that would be his eventual deliverance, Stallone was not yet out of the woods. He continued to struggle financially as he refined his newly adopted craft, even going so far as allegedly selling his dog for $50, just to make ends meet.

At age 28, Stallone was still living in squalor, had a kid on the way, and was already considering himself past his acting prime. But as he reached the end of his rope, divine inspiration finally struck, his muse taking the form of a boxing match between Chuck Wepner and Muhammad Ali. Though Ali won the fight, the underdog Wepner managed to land a blow that knocked The Champ off his feet. Stallone regarded this rare occurrence as a symbolic victory, even if it wasn’t a technical one.

Stallone channeled Wepner’s story into a screenplay about a similar underdog boxer, Rocky Balboa. The words poured out of Stallone and, just three days later, the 80-page script was complete.

Stallone knew he finally had something special and, after months of pitching his script, he finally had a studio interested in buying it. Though the specific numbers fluctuate a bit, depending on where you read the next part of this tale, we’re told that, despite his dire situation, Stallone balked at United Artists’ initial offer of $125,000. Then again at their offer of $250,000. Once more at their offer of $350,000. Stallone couldn’t let his script go without securing his role as the lead. This was a labor of love and a story that he intimately identified with, after all. Finally, UA agreed to his terms and cut him a considerably smaller check for $35,000.

A true testament to his character, the first thing Sly did with his windfall was buy back his canine companion he’d been forced to part with weeks prior, albeit at an exorbitant buyback price.

Stallone’s insistence on being the film’s lead came with another price, however. United Artists would now only be giving it a shoestring $1 million budget and forced a rushed 28-day production schedule with John Avildsen in the director’s seat.

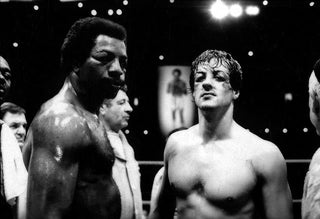

Carl Weathers and Sylvester Stallone behind the scenes of the film’s climactic fight. Photo: theeditroomfloor.blogspot.com

In the end, though, Stallone’s gambit payed off. Audiences and critics alike (mostly) loved the film and it became a smash hit, netting an 11,000 percent return on budget at box offices around the globe, with Sly earning 10 percent of the profits. The poor, deformed kid from Hell’s Kitchen had finally made it. He was set for life. Furthermore, the little boxing film went on to spawn a full franchise of sequels, netting over $1.3 billion at the box office. The forthcoming Creed II, the seventh movie of the series, looks poised to rake in even more.

But there’s one big caveat to this whole tale: much of it is potentially complete bullshit.

Stallone began tooling with his version of the Rocky creation myth right at its release. In an interview with The New York Times, he tells the bits about being down on his luck, his intense training regiment to become a great boxer in just five months, and drops the first mention of the bidding war over the script, (the bidding was capping at only $265,000 as he told it then).

“You know,” he pontificates to the interviewer, still merely on the cusp of the success that awaits both the movie and him, ”if nothing else comes out of that film in the way of awards and accolades, it will still show that an unknown quantity, a totally unmarketable person, can produce a diamond in the rough, a gem.”

But according to a 2006 interview with Gabe Sumner, United Artists’ head of marketing at the time, the entire story was merely “a tremendous publicity campaign.”

“I don’t have to tell you how the press feeds on the underdog story,” Sumner continued. “It filled up space on entertainment pages, and in columns looking for something for the next day. They ate up the idea that this actor loved his work so much, and was willing to sell it for a nickel and a dime in order to make it.”

To his credit, Sumner was absolutely right about audiences wanting an underdog stories, especially in that era. In 1976, America was a country aching for glimmers of hope. Though celebrating her bicentennial, the War for Independence marking the truest David vs. Goliath moment in the nation’s history, mid-’70s USA was reeling from a poor economy as its manufacturing era wound down and nursing the wounds from a failed decade-long war in Vietnam. These were sobering, dark times, and the public couldn’t get enough pick-me-ups in the form of the little guy taking on the world and winning against all odds. One only need look to the biggest hits of the decade to see the theme playing out over and over: Taxi Driver, Alien, and Star Wars: A New Hope.

In 1976, America was a country aching for glimmers of hope.

Furthermore, nobody has ever come forward to corroborate Stallone’s dog-selling story. In fact, its first appearance seems to be from a 2009 motivational site article before it went viral in a 2015 Facebook post. Presumably, just like the script sale saga, Stallone took what was likely a story about having to temporarily send his dog away while he moved and sorted some shit out and added some motenary flourishes for panache, flourishes he’s still including when he talks or posts about that dog today.

While Stallone’s physical and financial woes and dalliance in porno are by no means up for dispute, he is still a man who clearly knows how to spin a compelling yarn and, as Hollywood is an engine that runs on self-mythologizing, reinvention, and marketing, he and UA didn’t see any harm in adding a bit of razzle dazzle to the pitch.

But, having said that, so what? Why let the truth get in the way of a good story, right? These days, the tale of Stallone’s triumph against the odds and commitment to his dream is still being proliferated in all its juiced up glory, but it isn’t being used to garner press or sell tickets. Instead, you’ll find it being shared and retold by motivational speakers and life coaches urging on the struggling. Okay, and also dumb, clickbaity tabloids too, but whatever. At their cores, the stories of the Rocky script and Sylvester Stallone are still undeniably about the triumph of human resilience—even if a few scenes have been punched up a bit.

***