For nearly three decades, Father Greg Boyle—an American Jesuit priest and founder/director of Homeboy Industries, the largest and most successful intervention and reentry program in the world—has been helping gang members in Los Angeles rehabilitate their life and reintegrate back into society. A CNN profile from 2015 best explains Boyle’s motivation. In the interview, Boyle told CNN: “I’ve never met a monster. I’ve never met an evil person.” While many people would argue against that statement, it is this boundless compassion—another one of Boyle’s favorite terms—that has helped make Homeboy Industries a reality, and a place that makes room for people that most of society would much rather not deal with.

Boyle has another mantra: he believes that everybody is a whole lot more than the worst things they’ve ever done. Many who join Homeboy Industries have a lengthy rap sheet, but are also looking for a second chance. Originally started in 1988 as a program called Jobs for a Future while Boyle worked at Dolores Mission Church in Boyle Heights, California, Homeboy Industries has grown through the years and offers job training, placement assistance, and other free programs, creating a safe environment for their members to develop new job skills.

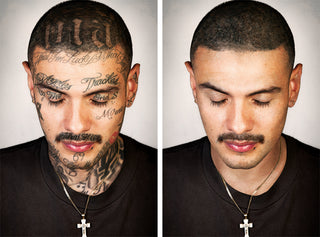

Homeboy Industries also offers case management, counseling, and legal assistance. While there are plenty of services and resources available, a lot of Homeboys still find it difficult for society to accept them for a simple reason: they have a lot of gang-affiliated tattoos in very visible areas on their bodies, making them an easy target to be judged. Several years ago, when photographer and author Steven Burton watched G-Dog and the Homeboys, a documentary on Father Greg Boyle and Homeboy Industries, he was intrigued by the tattoo removal program offered by Homeboy Industries. After the film, Burton went home, pulled up some photos of heavily tattooed gang members, and digitally removed the tattoos via 400 hours of Photoshop.

A clip from the documentary G-Dog and the Homeboys about former East L.A. gang member and artist Fabian Debora, now a state certified substance abuse counselor at Homeboy Industries.

The following day, he went to Homeboy Industries, and convinced several Homeboys to join him at his studio, where he should show them side-by-side photos of themselves, with and without tattoos. This was the origin story for Skin Deep: Looking Beyond the Tattoo, his new book released by powerHouse Books. Skin Deep is an exploration of tattoos as symbols for the gang-life scene in Los Angeles. The book features individual photo essays of Homeboys, where each of them react to the digitally altered images of themselves, free of tattoos, in full-length interview form.

In the book, the Homeboys, who want to turn the page and start a next chapter in their life, reflect and offer up personal anecdotes that are filled with from regret, resolve, and an appreciation for what Homeboy Industries has meant to them. Many of the Homeboys marvel at the photoshopped images, realizing that perhaps society would view them for more than just the gang-affiliated tattoos on their faces and bodies if they weren’t there at all.

Boyle once called gang involvement the lethal absence of hope, and the backstories of the Homeboys in Skin Deep confirm that statement. Francisco Flores is one of the Homeboys featured in the book. A two-page spread shows the juxtaposition of Flores with tattoos on his face and his right arm, wearing a white tank top. On the other side of the photo spread, Flores is in the same pose but now the tattoos have been digitally removed. “I’m changing,” Flores said in his interview. “But I think I would be more accepted if I looked like this, without nothing on my face or my arms.”

For Burton, the photos allowed the Homeboys to reflect on their life and be really honest with themselves. “All that bravado that built up over the years of being in a really tough situation or coming from poverty, having these walls built up to protect themselves, they were broken down right away,” Burton said. “You’re there and just talking to a regular human being in front of you, and all those things are set aside.” Flores details the first tattoo he got as a teenager, which was strictly out of anger towards his mother. He talks about growing up with his father, who was a drug addict, the violence he witnessed up close in his neighborhood at a young age, and the challenges of leaving his house and living on his own at the age of 15.

Flores has gone through an extensive tattoo removal process with Homeboy Industries, with six treatments on his face, nine on his neck, and seven on his hands. “I don’t have a problem with a lot of my tattoos,” Flores said in his interview. “It’s just I want my kids to have a better life.” The emotional reactions to the photos were something that stayed with Burton. “These people wake up everyday and see their history and violence staring back at them,” Burton said. “The violence doesn’t really represent them anymore, but they’re still stuck inside these gang tattoos and have to deal with everything that goes along with that.”

Skin Deep was a learning experience for Burton as well. “I strengthened my view that to judge somebody that you don’t know is just a reflection of your own ignorance in a way,” Burton said. “The people who were most successful at getting away from gangs were the ones who have been taught to love themselves, to deal with their past and put it behind them, and come to terms with who they were. Only at that stage can they really progress and start making better lives for themselves and stop the cycle of violence for their children, which was a big deal for them.”

Father Greg Boyle in 1990 with members of the “Clarence Street Locos” at the grave of a fellow gang member. Photo: TNS photo/Anacleto Rapping, Los Angeles Times.

Burton has also developed an admiration for the work that Boyle does. “I’m not a religious person, but when I email Father Greg, it’s like having a direct line to God,” Burton said. “He’s an incredible person.” Despite the work of Homeboy Industries and honest attempts for their members to rehabilitate, transitioning back to society and breaking the cycle of violence remains a difficult task. We’re also reminded of this inescapable truth in Skin Deep.

Vinson Lee Ramos joined a gang at the age of 13. When he spoke with Burton, Ramos was working as a contractor for an environmental company cleaning storm drains. “Nobody knows what will happen tomorrow,” Ramos said in his book interview. “I am just living day-to-day, hoping for the best, moving forward. I have to support myself, hopefully out for good.” In July of 2016, Ramos was shot and killed by police officers. He was 35.

The subjects in Skin Deep react to seeing photos of themselves without tattoos for the first time.

Calvin Hastings got his first tattoo when he was 12 years old, and met Boyle for the first time shortly after at Hastings’s first communion. In his interview, Hastings talked about an incident where he was shot which left him paralyzed and in a wheelchair. “I was in the hospital for around nine months and that’s just because of the surgeries, then the physical therapy,” Hastings said. He talked about wanting to work in a mental facility as a goal. In June of 2016, Hastings was shot and killed in Vernon, California. He was also 35.

Ramos and Hastings are just two of many people that Boyle has buried through the years. Despite the encouraging number of Homeboys who do rehabilitate themselves and reintegrate back into society, there are still many challenges that remain. Boyle, in an email exchange, expressed his excitement at Skin Deep. “Anything that puts a human face on the gang member is a good thing,” Boyle said. “One always hopes that people will stand in awe at what these homies carry, rather than in judgment at how they carry it.”

Boyle says funding remains challenge for Homeboy Industries, and there are still barriers to finding permanent job placements and places who are willing to rent to the Homeboys. In a 2015 Los Angeles Times article, Boyle talked about layoffs and the financial challenges at Homeboy Industries. I asked whether things are better now. “More stable, but always difficult,” Boyle said. “If we were a shelter for abandoned puppies, we’d be endowed with a huge reserve. But we help tattooed, serious and violent offenders. It’s a tough sell, but a good bet.”

Boyle has been making that bet for decades. For a society that refuses to view these gang members through a more complicated lens, Skin Deep allows for a different and more layered perspective.

***

Buy Steven Burton’s Skin Deep from powerHouse Books here.

Learn more about Homeboy Industries and how you can help at homeboyindustries.org.