Dismaland (The UK’s most disappointing new visitor attraction) was Banksy’s biggest and most ambitious project so far. A temporary amusement park constructed in the seaside city of Weston-super-Mare in England, with 58 artists and the elusive street artist himself showcasing some amazing pieces of work. The six-week pop up exhibition is now over, but the movement continues, as all timbers and fixtures leftover from the park are being repurposed at a refugee camp in Calais to help build shelter.

Lee Madgwick is a painter from Ely, Cambridgeshire, and one of those 58 artists who had their work featured at Dismaland. If you think landscape painting is not-a-2015-thing, you’d better get accustomed to Madgwick’s work—and take a closer look. Things are not always what they seem.

MANOS NOMIKOS: How was taking part at Banksy’s Dismaland? A bit of surprise getting the call from Banksy? I am sure you don’t know who he is, right?

LEE MADGWICK: It’s still pretty hard to believe really. It has been a great ride, being part of such an audacious, top-secret project as this has been an incredible experience. I genuinely thought the whole thing was a hoax at first when I received the first email—my finger was hovering over the delete button for a while. It was only after a little research that I realized it was bona fide. I’ve hugely admired Banksy’s work for many years, so it took me back a bit knowing he also likes mine. Maybe I’ve met the mystery man himself, maybe I haven’t. I genuinely don’t know.

“[AS AN ARTIST] I’VE LEARNED THAT THERE’S ALWAYS TOO MUCH TO DO, THAT I’M ALWAYS RUNNING BEHIND, AND THAT I NEED TO PAINT FASTER.”

Tell us some more about your pieces at Dismaland and what they represented in the park?

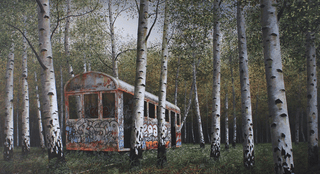

My paintings are generally moody and atmospheric and these pieces are no exception; these paintings are a mix of urban and rural settings. One featuring an inner city tower block neatly seated in a picturesque verdant valley, whilst another shows a typically British street where colorful balloons mysteriously emanate from an alleyway between two houses. One painting features an abandoned, graffiti-strewn rail carriage in a dense birchwood, and the last painting depicts a neglected Internet cafe nestled within a meadow where there are hints of ruined neighboring buildings; like a relic of a bygone age and the only “social networking” taking place is by a couple of pigeons sitting on the window ledge.

Did you get any guidelines of what pieces they needed, or it was absolutely free for you? How much time did it take to finish your works for Dismaland?

As I only knew about Dismaland roughly five or six weeks before the opening, I didn’t really have enough time to complete many new pieces. “Inconvenience Caused” (the train carriage in the birchwood) was a piece I had just started, so luckily this, along with three others that I had available, were chosen. Banksy was especially keen to add “Social Networking”—which is on loan—as he enjoyed the humor in it.

Did you see the other pieces at Dismaland? Which left the biggest impression on you?

I was lucky enough to see Dismaland on the private view night. It’s hard to pinpoint one thing that stands out as the entire venue is packed with thought-provoking and engaging works. Although most pieces are politically charged, the humor throughout is quite brilliant. The most poignant piece was, without doubt, the remote control boat pond where the boats are full of refugees. You can put money in a machine to control the boats and the destiny of the refugees. In contrast, the Grim Reaper in a bumper cart bopping along to the Bee Gees’ “Staying Alive” track was pure, unadulterated good fun. The eclectic paintings and installations by the likes of Josh Keyes, Ronit Baranga, Zaria Forman, and Damien Hirst complemented one another perfectly. Jimmy Cauty’s monumental post-apocalyptic model town was a piece to behold.

“WHO INHABITS THESE PLACES? WHAT LIVES DO THEY LEAD? WHAT IS HAPPENING OR ABOUT TO HAPPEN?”

What kind of things did you draw when you were a kid? Did growing up in East Anglia play a big part in shaping your worldview and art form?

I must’ve been born with a pencil in my hand—I drew anything and everything. I was even an early graffiti artist too if you consider a rogue toddler scribbling on every wall in your parent’s house a graffiti artist. I’ve always enjoyed drawing buildings of all kinds. As far back as I can remember, this played a heavy part in my creative process, where I quickly developed a detailed architectural pen and ink style. Over the years, it has just evolved into something darker and more surreal. My home county of Norfolk, England, has played a major role in my work, probably more subconsciously than anything else. I’m constantly drawn to the big moody skies, country estates, and vast beaches. I’m obviously biased, but it’s a beautiful part of the world.

In most of your pieces, we see scenes of abandonment set in rural British landscape. Are there any stories or narrative behind your work?

Each piece has its own narrative, which is an important part of my work. I intentionally never fully explain it, I like to leave it for the viewer to come up with their own interpretation. Many of my paintings have an undercurrent of mischievous menace, where the subject matter is at once thrown into question: “Who inhabits these places? What lives do they lead? What is happening or about to happen?”

There’s certainly a post-apocalyptic, sedately surreal air about them, yet can also be subtly topical, political, or simply touching on current trends. There’s also something oddly pleasing about juxtaposing an urban scene in an isolated rural landscape.

Do you also enjoy traditional landscape art?

Most certainly. There are many artists I admire, from Constable to Magritte to Hopper, as well as relatively unknown artists like Leonard Squirrell and Walter Dexter. But time and again, I am drawn back to the great Northern European artists from 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, including Casper David Friedrich, Jacob Van Ruisdael, and John Crome. The atmosphere they created with dark, earthy, moody tones are captivating.

Would you describe your style and methods?

I paint the skies in oil with my hands and occasionally a car sponge—for some reason. After a few weeks, they are dry enough to set to work on the detailed foreground using acrylic paint. Creating a moody, intimate, and atmospheric setting plays a major role in the narrative that I aim to achieve. I have a fascination with abandoned, dilapidated buildings and you will usually find some kind of dereliction in my work. I hope to create mysterious, intriguing, and sometimes quirky pieces that evoke a modern fairytale-type dystopia.

What have you learned along the way being an artist?

I’ve learned that there’s always too much to do, that I’m always running behind, and that I need to paint faster. Above all, the most important thing I’ve learned is to be true to myself, to be honest in my work, and to perhaps believe in myself a bit more.

Last but not least—probably a question to made in the beginning—what are you working on right now and what’s next for Lee Madgwick?

I’m currently working on a small body of work for a mixed gallery show in London—again, I’m a bit behind with this. Also, I’m being kept busy with illustration work for a new sideline project that my wife—also an artist—and I have recently set up. We’re frustrated doodlers and needed an excuse and outlet for this, so greetings cards seemed like a good idea—therefore, ScampletandBee.com was born.

***

Keep up with Lee’s latest at leemadgwick.co.uk.