We all wanted Acme products.

The Nerf weapons and Mousetrap games we got as kids were poor substitutes. I remember watching in wonder as Acme Portable Holes were demonstrated “in real life” in Who Framed Roger Rabbit. I wondered what would happen if you jumped into one; where you would go. The possibilities twisted my mind into knots like some kind of Kidz-Bop Stephen Hawking.

Acme was our first Hogwarts, the place where magic came from. Every time the Toons needed to put an improbable hold on the laws of physics to accomplish a gag, Acme was there. And crucially, especially in the hands of the Coyote, Acme products often served comedy by failing.

Failing miserably.

Behold: literally eighty different booms in eleven minutes, courtesy Acme explosives’ phenomenal failure rate and a certain inept desert mammal.

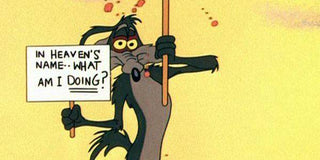

The bizarre mystery of Acme is also the mystery at the center of all the best physical comedy: How can something be so awe-inspiring and fail so totally at the same time?

What exactly does it mean to “fail spectacularly”?

When we’re watching the coyote construct these elaborate scenarios, we know what’s coming. There’s no doubt in our minds. We harbor absolutely no suspicion that he’s going to catch the Road Runner this time. So what dictates our engagement? Why do we still love to watch?

We want to see how massive the coyote’s failure will be. We want to see the precise mechanism of his failure—to see how high the cartoon’s writers and artists can build the pyramid before tearing it to the ground. We thrill at the imaginative ways they bend physics, suspend expectations, and pile on the pain. They’re the sculptors, and Acme products are the clay.

We want to see how massive the coyote’s failure will be. We want to see the precise mechanism of his failure.

We also love to watch the predator lose. Through a sort of narrative bait-and-switch, we see the Road Runner as the underdog—even though he triumphs every time, and causes the coyote no end of pain while doing so. The coyote is trying to kill him, after all.

The YouTube channel Every Frame a Painting does this great analysis of Jackie Chan’s genius at physical comedy, and we see the same principles there. Just like with the coyote and the Road Runner, it’s important that we see the pain and struggle clearly and sharply. In both Chan’s work and the Road Runner cartoons there’s an almost musical rhythm to the pain and suffering (frequently assisted by an actual orchestral score in the Coyote’s case). It’s like a ballet. The payoff is earned; there’s a buildup and a crescendo. We’re given a symphony of failure, failure that is a delight to consume.

Witnessing failure, witnessing the spectacular degree to which humans (and coyotes) can fail, is culturally important. We live in a world filled with large, powerful institutions, and we often feel powerless next to them. Acme means, hilariously and ironically, “the peak”: the best product. The name was chosen to skewer a particular brand of ’50s consumerist ubiquity. The Looney Tunes Acme Corporation is clearly an Amazon-style conglomerate, large enough to supply every product in existence along with some that couldn’t possibly exist. Yet this massive company’s output produces hilarious calamity just as often as it produces functional convenience.

Witnessing failure, witnessing the spectacular degree to which humans (and coyotes) can fail, is culturally important.

When we witness Acme failing, we remember, crucially, how bad everyone in the world is at everything. We tend to think of giant corporations as invincible, robotic entities, and when we consume the news it can feel seductive to think of ourselves as pawns in massive geopolitical games that are beyond our control. Taken to the extreme, this thinking becomes conspiracy theorism. But like Alan Moore, the writer behind The Watchmen comic and a corporate and political satirist in his own right, says:

“The main thing that I learned about conspiracy theory is that conspiracy theorists actually believe in a conspiracy because that is more comforting. The truth of the world is that it is chaotic. The truth is that it is not the Jewish banking conspiracy or the grey aliens or the twelve foot reptiloids from another dimension that are in control. The truth is more frightening: nobody is in control. The world is rudderless.”

This rudderless blindness is aggressively and repeatedly demonstrated by the Acme corporation. They continue to exist in and dominate the Looney Tunes universe, and they continue to fail. Through this, we can laugh at the fact that an organization’s size and power are feeble proof of its efficacy. Walmart, Facebook, and Apple fail us in tiny ways every day, due to basic stupidities: late delivery trucks, apps that don’t work, parts that can’t be replaced.

Many of these large businesses rely on failure as an integral part of their business model. They have so much money that it doesn’t matter. Google is constantly creating projects, then scrapping them when they don’t work, burning through money in an effort to win the innovation lottery. We notice none of this, because we aren’t meant to notice it. In the rare instances that a failure-prone product like Google Glass does make a splash, it becomes just as much of a public joke as any dysfunctional Acme explosive. Like Acme, these companies are monolithic not because they are run perfectly or because they always succeed, but simply because they have money to flush down the toilet. They’re “Too Big To Fail,” even though they fail all the time.

But the crucial difference between those companies and Acme is that with Acme, we’re able to see the failures clearly. When the Coyote swings a wrecking ball down between two canyon walls, and it swings straight down, up, over, and lands directly on his head, missing the Road Runner entirely, the mechanism by which it failed is obvious to us. We laugh because we see the stupidity, we see the failure in process. We sense it coming a moment before it happens, and we laugh at the obvious lunacy of Acme’s failed design and the Coyote’s failed execution.

With huge companies, tech and otherwise, this is much harder, not only because they hide their failures from us, but because the mechanisms failing are often too large and complicated for us to understand. Our online activities, real-world job security, our choice of supermarket produce—we have no real idea what governs any of it or how it works. So when those things fail, instead of their failures feeling funny or absurd, they feel vaguely menacing, like we’re subject to shadowy forces that are beyond our comprehension or control.

It’s important to remember our own fallibility, and to have a sense of humor about ourselves and our fellow human beings.

To combat this, it’s important to remember our own fallibility, and to have a sense of humor about ourselves and our fellow human beings. We have to remember that all these companies are comprised of people much like us, people that make mistakes all the time. They’re not somehow fundamentally better than us; they have lazy days and do stupid things too. And the more we learn about our world and how it works, the more a failure on the part of Facebook or Amazon will have the same clarity as an anvil falling on someone’s head.

Shows like Silicon Valley are important for this reason—they let us laugh at the corporate and technological forces that rule our lives. They help us to see these companies not as omniscient and obscure forces of nature, but instead as vaguely silly founts of occasionally useful garbage—just like the Acme corporation.

***