Gook – n. an informal, offensive term used against people of East and Southeast Asian descent. It’s also the title of writer/director/star Justin Chon’s startling new film, and for a specific reason: it’s meant to be confrontational. It’s meant to shake you awake to a reality that history’s forgotten. You have no choice but to pay attention.

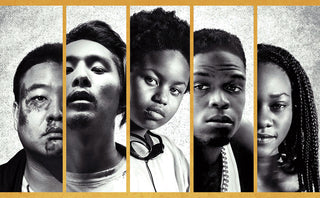

Distilled, Gook recounts the Korean-American experience during the 1992 L.A. riots, a perspective rarely if ever told, let alone depicted on screen. Chon stars as Eli, a shoe store owner struggling to run his family business with his brother Daniel (David So). They befriend a young black girl named Kamila (Simone Baker), who works at the shop and serves to bridge the gap between the black and Asian community, here embodied by Eli and Kamila’s brother Keith (Curtiss Cook Jr.). As the city of Los Angeles unravels at the news of the Rodney King verdict and sets itself on fire, so does the story of the film, with brewing tension between the Asian and black communities coming to a boil by film’s end.

It’s a tale that hits close to home for the writer-director, as Chon’s family business ended up falling victim to the looting and chaos of the riots about 25 years ago. In fact, Chon’s father plays a key role in the film, starring as Mr. Kim (Sang Chon), an antagonist who embodies the simmering resentment between races.

The Hundreds caught up with the writer-director on the heels of the film’s release to discuss its significance during the Trump era, the forgotten history of Asians in the U.S., and how growing up Korean in Los Angeles shaped his identity.

What inspired you to make the movie?

Over the 16 years that I’ve been an actor, I’ve auditioned for a few L.A. riots films and none I felt were accurately representing our issue. The Koreans lost the most financially, besides the city of Los Angeles, yet we’re not at the table for the conversation. So, I took it upon by myself to tell it from the Korean experience.

How did the riots shape your childhood?

I was 11 and at that age, you process it differently. It’s just more immediate things like: Does this mean I have to change schools? Does this mean I have to make new friends? And Asian families don’t talk about trauma. We just power through. We don’t have family meetings, so it just kind of passed. But through the years, I’d ask my dad about it and he’d be very tight-lipped because he didn’t understand why I was asking.

“Where do we fit in? Do we even belong here?”

When I told him I wrote this role for him to play, he was confused. He was like, “Why do you want to revisit such a traumatic experience? It’s the past, let’s move forward.” It took me awhile to make him understand that.

As Americans, and human history in general, it’s important that we revisit these things because we can’t erase our history. We have to educate people that Asian-Americans are part of this country as well.

I was reading this angry piece about how Asians appropriate black culture. But to me, coming from immigrant parents who were so focused on building their lives here, I and the other first-gen kids I grew up with in LA had to create our own cultural identity by piecing together what we saw around us—and that was hip-hop, R&B, street racing, etc. Sometimes I feel lost about my own identity because it’s such a mix of everyone else’s. That said, what was building your identity here in SoCal like for you?

100%, absolutely. The appropriation thing—I understand the argument and I guess it’s a fine line to walk to discuss something like this, but I’m sorry man, we didn’t have our own shit. We didn’t have our own musicians that we could look up to. Who do we have in media? There’s Steve Park in In Living Color but really? That’s the guy we’re looking up to? We don’t have anyone!

It wasn’t in this sort of lascivious, ignorant way; we just didn’t have anyone to cling onto. Growing up, I listened to rap and R&B. You see it in this film: Daniel (played by David So) wants to be an R&B singer, not because he’s trying to appropriate the culture, but because that’s what he identifies with. And it’s not like he lives in some really WASP-y area and making a conscious effort to appropriate it. He’s living in the hood and that’s the culture he’s exposed to.

In my later teens and early 20s, I was so into underground hip-hop. At that time, it was Hieroglyphics and Zion I and People Under the Stairs. That’s the weird thing about being Asian: we’re just invisible, and because we’re invisible, no one cared until now. We could identify with white culture or black culture. Some, we identify with Hispanic culture. I have a friend who grew up in East LA; he was the only Korean person on the street and he thought he was Mexican! We just adapt to whatever is available to us. Even with Bobby Hundreds, I’ve kept up with what he’s interested in and he really identifies with punk and skate. I don’t necessarily know if there’s any negative connotation behind that.

Not at all. It all comes from a really sincere place of just trying to find yourself.

We’re just lost kids trying to figure it out.

It’s not necessarily motivated by race. It’s motivated by individuals just trying to piece themselves together.

Absolutely. And we’re across the board in our interests.

Growing up, how did you experience LA? What were those racial relationships like?

Back in the day, my family community was so insular. Your experience with the people you interact with through your family is mostly within your ethnicity. But at school, I had friends from every race and creed. We all just hung. It wasn’t as sensitive as it is now. I’m not saying it’s OK, but you just dealt with it. You see it in my film; it doesn’t affect them because it’s just everyday shit.

“If we create fully dimensional Asian characters, we won’t be embarrassed.”

There’s this conversation now about how hate is learned and I believe that, because when I was a kid, I didn’t hate someone because they looked different from me. You don’t even think like that as a kid. But as you get older though, you get more conscious of it. Especially in Asian culture, there’s a lot of self-hatred, like, “Oh I don’t want to hang out with other Asian people because my friends are all white.” You know that kind of mentality?

Oh, definitely. Being “whitewashed” was a compliment growing up. Why do you think that is? Why do you think Asians sometimes don’t want to be associated with other Asians or Asian culture?

I feel it’s what we saw as cool growing up. And this goes back to how we are represented in media. It’s because everything we see on TV points to white kids being so cool and Asian kids being nerds. This is the exact reason why how we are represented is important. It creates our perception about the world around us. If we create fully dimensional Asian characters, we won’t be embarrassed.

The release window of this movie is crazy. It’s coming out at both an excellent and awful time. It blows my mind that now more than ever do we have to assert our Americanism.

Absolutely. When we go to our motherland, they don’t consider us from there. They consider us American. But here, we’re considered as from another country. What difference is it if you’re Irish and your parents came here? We’re the same. Just because of the color of your skin you’re more welcome? That’s crazy. We do have to assert ourselves.

The other thing is that we helped build this country. We weren’t brought here through slavery, so there is definitely a big difference there, but we have been here for a long time. A lot of people don’t know, but we were here through the Civil War. Chinese people fought at Gettysburg. We have to make sure that we’re accepted.

You should tell that story!

I know someone who’s doing it and I hope they get it made. But it’s very hard to get a film like that made. [Laughs.] But also, you’re talking about the times right now, but to me, is it unfortunate? I don’t think so. It’s necessary because it was just laying dormant. Now, with Trump, we’ve exposed it. Now, we have to fucking deal with it. Let’s fight it out. Let’s argue. Let’s figure it out. What’s scary is that it was there the entire time.

On set with Simone Baker, the young actress who plays Kamila, what were your conversations with her in regards to the message of the movie?

We rehearsed for over a month and a lot of that rehearsal was hanging out and getting comfortable with each other and talking about race. Her mom was integral because she needed to also prep her and let her know the history of racial conflict, the LA riots, and why it happened. There was a lot of people who helped get her ready.

“The biggest influence of this film was La Haine.”

What about with Curtiss Cook Jr., who plays Kamila’s older brother?

When he read the script, he was like, “I’m in!” But then the next part of the journey was us exploring what it means for him as a black man. Last thing I wanted to do was perpetuate the stereotype of “angry black man.” That’s why I hired him; he’s so three-dimensional and has such depth and sensitivity. At the same time, we talked a lot about what everything meant.

The thing is though, Eli and Keith are the same character. They both are orphaned, they both need to be responsible for their younger siblings, and they both are aggressive and angry. But we had long conversations about what it means to be Asian and black in America and the responsibilities we both have with our art.

What are those responsibilities?

This always changes as an artist, but the phase I’m at now, I think about through the perspective of having a family. When I bring a child into this world, what is the world that I want them to live in? I’ve been thinking about my value as an artist. I could be selfish and just make things I think are cool and more expressive about the human condition in general. But, because I have this very specific viewpoint being an Asian American man living in the U.S., that perspective is so valuable because we don’t have enough of it.

It’s not something I set out to do when I first started acting, but I’m starting to realize that people are craving it and needing it. I don’t necessarily know if I wanted to have that weight on my shoulders, especially with this film, but a lot of the Asian community have been saying how they’ve been waiting for something like this. That’s important right now. So if I have the skills, the perspective, and the unique vision to make [that kind of art], then that’s where I’m best served. Year after year, when you find yourself limited to certain roles, you realize it does matter because your art is being directly affected by this.

“We’re just lost kids trying to figure it out.”

I know it sucks when you’re a person of color and you can’t escape the discussion about race in your work. But, especially with this movie, you’re playing a strong, tough, Asian man and people aren’t used to seeing that. Like you said, who’s gonna shift the perspective if you don’t?

Rarely do I get asked about craft. I did this talk with Ava Duvernay and she wanted to talk about craft since we never get to because we’re always talking about social and racial issues rather than, what kind of camera did you use? What was the idea for the anatomy of the scene? It gets tiring, but I’m realizing that if I can use any cache from this film, might as well tell someone’s story that doesn’t have that opportunity.

Right now, my next film is about Korean adoptees who come here when they’re three and get deported at fortysomething, when they’ve already had families here. They didn’t come willingly to this country and now after having something to lose, we’re kicking them out. That’s nuts. Adoption is as American as you can get and we’re a part of the system that’s creating these individuals, their situation, and we’re totally just neglecting them. But those are the types of stories that if I don’t do it right now, then who will?

I’m gonna end this with a craft question.

Thank you!

Aesthetically, how did you want to depict LA?

My biggest thing is that I didn’t want to sensationalize anything. The visceral feel of what it’s like to hang out at the store, I wanted that. Also, there’s this old black-and-white film called The Last Picture Show and it’s set in a rural Texas town that feels very secluded. I wanted it to feel like that, like a Western in a way.

“Displacement… that’s how [Asian-Americans] feel growing up in this country.”

At night in that part of town, it’s just quiet. No policemen, no firemen, nobody’s coming here to help these fuckers, man. That’s what it felt like, and during the LA riots, that’s what happened. No one came to save them. They were left to deal with each other. The black-and-white was on purpose to make you focus more on the relationships, and the aesthetics fade away. The biggest influence of this film was La Haine; in that way, I just wanted to hone in on the relationships and make it feel very intimate.

I like the way you play with space in this movie. In that, there’s a lot of emptiness and silence that are filled with a simmering tension.

To credit my DP, he helped design that.

I thought it was interesting because that ties back into the invisibility you mentioned earlier.

I have this running theme through my work of displacement. It’s definitely very prevalent in this, and it’ll be in my next movie—that’s how [Asian-Americans] feel growing up in this country. Where do we fit in? Do we even belong here? Because we don’t belong in our mother country anymore.

***