Ash Thayer was only 19 years old, living in New York City and attending School of Visual Arts on student loans and grants, when she found herself out of money and more importantly, out of a place to live. She moved into the now legendary Lower East Side See Skwat, and spent the next six years, from 1992-1998, bouncing around the city’s various squats and becoming a full-time member of a community of squatters that society chose to overlook. She continued to study photography at SVA during this time, and captured hundreds and hundreds of powerful and beautiful images of the people in her world, set against the backdrop of the city’s abandoned buildings where they lived.

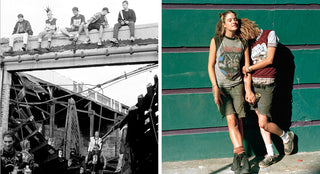

Many of those photos appear in Thayer’s book, Kill City, released earlier this year via powerHouse. A selection of these gripping, gorgeous images will be on display at Thayer’s show here in downtown LA at Superchief Gallery this Saturday, September 19th. I got the chance to interview Thayer about her time spent living in these squats, her community, and what she hopes people will take away from her book and photos.

YASI SALEK: You were attending school at SVA on scholarship and financial assistance when you got kicked out of your first apartment because you ran out of money. How were you accepted at first in the squatter community? Because you were technically an outsider, right?

ASH THAYER: There was so much crossover with the young punks that I knew that were squatting, we were all going to see the same shows at ABC No Rio and just the different punk DIY venues. We were around each other a lot. There was a community based in music and also in protest culture and in places that gave out free food and Kim’s Book Store, where you go and look at records… There were spots where people like us sort of socialized.

So it wasn’t that big of a deal, it was just someone had space, part of their apartment that was empty, and people were generally really good at getting them filled because it also meant that you had an extra set of hands to work on the apartment or the building. And people were just kind, like, “Oh that sucks dude, you’re screwed? Come stay with us for a while!” I guess it just happened kind of naturally. I act tough but I’m kind of smiley and kind of sweet and maybe that just helped.

When you first started documenting stuff everything around you in these places, did you come across any resistance at all from your fellow squatters?

No. Sometimes I was just like, “Ah how do I use my camera? How do I make an exposure in this darker environment?” You know, I was kind of doing my class work, but then any way I could I would fudge my assignments into just photographing anything I wanted to photograph, which was where I was. I was so very singularly focused on being a part of protest culture and activism and feminism and just being politically active that I wanted to devote every frame, every breath, every purchase I made, you know? Annoyingly so I’m sure to some. But it was an obsession.

I knew if someone didn’t want his or her picture taken; I’m very intuitive. Some people might take time, but I didn’t have the strategy like one day I’m going to get to this person then one day I’m going to get to that person, It happened more naturally, like if I was hanging out or there was a work project we needed pictures of, and then eventually when I was living with people and we became friends, if anyone gave any flack I’d be like, “Shut the fuck up, I need these pictures.” I’d say, “Twenty years from now, you’re going to be thanking me,” and literally that happened! It was really cute. One of my friends Pat, he was like, “You know what? I used to bitch about you taking pictures and I would bitch about it to other people. But I just wanted to say I’m sorry and thank you. I’m so glad you took so many pictures.”

That actually leads into another question I had—do you keep in touch with a lot of people you lived with in this community?

Yeah definitely. With the book, I was originally just going to make it into a little zine or something, because I was sitting on all these memories of all these people, this time and history that there hasn’t been given enough historical legitimacy to. You couldn’t go to the library or the New York public system and look up or find a history of these people and what happened. There are very small museums of resistance out in the Bronx but they’re so hard to find and you have to really know what you’re looking for; you’re not going to stumble across this. So I wanted at first for the book to be for the people who are in it. It was such a burden to have the memories… It felt like I was holding too much and wanted to give it back to them like, “Here, they are yours. Look at us, look at what we did. This is my gift to you.”

I had offers to publish before, but they were usually by weird men in the art world who wanted to sleep with me, or teachers who wanted to sleep with me, or people who wanted to change it into their own agenda… It would have been a totally different book, and I was like, “Fuck you, man!” This book is about resistance to ALL that and doing it yourself and maintaining your integrity and not at all compromising the subject matter so fuck off, no. I’ll sit on it forever and maybe my kids will publish it someday.

Was there any point when any of your professors showed any concern about your living situation?

Yeah, one of the school counselors called my mom and told her I was on drugs and that she should come get me… I think they tried to kick me out, like I lost my scholarship… a lot of my teachers made fun of my work. They didn’t even like it. They would help me in terms of portraiture and the gray scale and the zone system and shit like that… But they didn’t care what I was doing. They made fun of the work, they made fun of the kids… I didn’t get a lot of encouragement. It just felt discouraging and somewhat predatory. I did get some encouragement about the way I was making documentary photographs. But they were totally not interested in the subject matter. They wanted me to stop photographing scrappy-looking punk kids.

Right. They wanted you to shoot something more beautiful…

Or just a different topic in general. But then Raghubir Singh, who is an incredible Indian photographer, was very encouraging. He came over to the squats one day, he gave me a flash. He was like, “Ashley you need to get these exposures better, these are blurry.” He was just like a big brother, and he would meet with me and edit pictures and give me guidance and he was really great. He passed away when he was 54, right after I finished school. It was very devastating, but he was a great mentor.

You spoke to this a little earlier about how important feminism is to you, and to the punk movement in general...as a young woman did you ever feel like in danger in any of the squat situations, or were you always kind of in an environment where you didn’t have to feel worried in terms of sexual assault?

I never experienced that. I slept with doors open. I got drunk and blacked out and passed out, that sort of thing. I never had anything happen to me, and that’s the experience with most people that I know. And if anything ever did happen, people would probably get their ass kicked. We would take care of it ourselves, that sort of thing. But I would say that I have, in recent years, heard of cases of some domestic violence that happened that I was unaware of at the time. There wasn’t a large amount that happened, but there was violence. Some people were definitely addicts. But I don’t have much information on that. I would say in general it was a really safe environment. For me it was. I felt safer there than on the street.

You’ve mentioned that you were already deep in the punk scene starting in high school, when you moved out of our parents’ house when you were 16. Do you feel like that made you more drawn to the squat culture? Because it’s so fundamentally anarchist, anti-establishment, and do-it-yourself, and in that way reflects the ideology of that era of punk rock?

It was a very smooth transition. The squatting scene in New York was a unique time and place. This type of community in this type of city-owned buildings all in such a small area, it was an anomaly in a city environment. It happened because of the way that tenement houses were built when New York was first settled. They were the slum houses for the immigrants. So those areas were very hard to bust up and very hard to sell to developers as they started developing New York. You ended up with all these empty, kind of shit buildings. We took them over. And we would be able to run over to each other and help or lend tools or cook meals. I think it was very special because of that.

How did you find the drive to continue your education when you had this kind of a hard life? You were scrambling to find food some days. How did you manage to not ever say, “Fuck it I’m quitting school”?

I think I knew that I was learning a skill that I could use, and I was living on student loans anyway. It was borrowed money. And I just believed that it made more sense to get the education and get the other stuff later. I wanted a degree. I wanted to finish. I didn’t want to end up waitressing forever because I wanted to kill people that I waitressed for, you know? I wanted to have my own business someday.

You wanted to continue to DIY.

Yeah! I didn’t know what I wanted to do with photography because I hated fashion and the commercial work they were teaching us. The last thing I wanted to do was photograph some anorexic girl with a $5000 outfit on.

How did you ultimately transition out of this squatting world?

I needed to get sober. I was drinking then very heavily. It was time for me to get sober and I couldn’t do that there. It was just not the situation that I could do it in. I had gone through depression and I knew I had a problem [with] drinking and wanted to quit. And I also wanted to get out of New York for a while. I had been a part of the struggle and just within the protest culture I needed a break. I wanted to see what else was out there.

It’s been 17 years since you lived in those squats. When you look back what do you miss the most about your life? Living in that world?

I miss all my friends and being able to just hang out with them daily. You know just waking up, cracking jokes, doing projects together. Just the camaraderie. We had water balloon fights, just fun things that most adults in general don’t get to have if they lack community. The sense of community is really important to me, which is interesting because I’m also a really big isolator. Like I can isolate for days on end, but it’s not healthy for me. So I love being around people even if they annoy me. But yeah, just being a part of people’s lives and being able to help each other out and hug each other. The girlfriends were priceless; we helped each other get through so much stuff.

When people look at these photos and bodies of work, what do you want them to take away from it? What do you want them to see when they look at these photos?

I want them to be inspired to do something in their own lives that would be of service to people without housing and people who are in need of just daily necessities. I want people to be inspired to come up with different ways of living. I mean everyone looks super cool and thrashed out and punk and fun and the style looks very good. Those are some good-looking kids with some very original get-ups going on. But ultimately I want the millennials to think, “Hey, there are lots of city-owned properties and the city isn’t doing anything with them. There are a lot of homeless people that would like to do work. How can we put those two together?”

For example, My friend Stephen DiCaprio is a squatter advocate. He is working toward developing city-owned blocks of land with organic micro-farms that will feed homeless people, and will also house them. They can make shacks up to 150 sq, but they are like, little cabins. They run off solar power, so it’s a barter system where the homeless person who gets to move in has to farm the land. The land brings a profit and provides food, and the city becomes a greener place. This is happening in Oakland but we would like to see this happen all over California. Why not?

With so much homelessness and people in dire situations, sometimes people shut that down because they feel powerless, they don’t know what to do. But hopefully this book is both challenging and interesting, and also fun. I get inspired by fun things too. I need some excitement with my inspiration. I hope people are inspired to take some action, and to know that you don’t need to look like a punk rocker to do it, you can look like a total nerd, it doesn’t matter. There are so many ways of making the world a better place. Serving people really is one of the most joy-creating activities that you can do. So instead of hitting the bar, go help some people. You’ll feel a lot better.

What are you working on now?

I’m still an artist. You can go to my website and see my bodies of work I’ve done since then. Right now I’m doing a series of female warriors. A lot of my characters are from the LARP (Live Action Role Playing) community. And they are people that I go out and play with. I also have a series of male sirens, and I’m interested in looking at the way we have traditionally sexualized women and heroicize men. That project basically flips the script but also makes some damn good-looking images. They are triptych pieces and I photographed a lot of those in Ireland.

***