When I first catch Chris Stewart on the phone, he sounds on edge. And for good reason—his first album as Black Marble in three years (It’s Immaterial) was dropping the following day, and his album tour began that night.

“Is this still a good time to chat?” I ask, as I always do.

“It is...” he says with a tone that suggests it isn’t. “Unless we can do 3:30 instead. I’m kind of having a crisis.”

After he explains a sound issue I don’t totally follow, I say no problem and we reconnect later that afternoon. When I catch him again, the edge hasn’t dissipated, and again it makes sense. He’s in the car on the way to pick up his friend Oliver, with whom he performs live (Stewart writes, records, and mixes all of Black Marble’s music himself) to drive to Riverside for the tour’s kick-off. I see him perform three days later at the Echoplex.

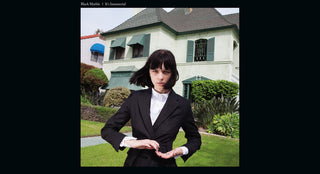

The show’s crowd reminds me of the recent album’s cover art, which depicts a glaring hipstress afront a light green house in suburbia. With her blunt black bangs, black suit, and black fingernails aligned in a manner that almost suggests witchcraft, the woman would fit in well at the Echoplex that night. This makes sense because Stewart sees the woman, shot by photographer and friend Logan White, as “the Patron Saint of the record.”

“She looks like a cool, weird girl who lived next door to you in high school and never went outside,” Stewart tells me on the phone. “She’s mysterious looking. I imagine she listens to records in her room. I feel like that’s her house and she’s kind of stuck there.” Stewart says the photo reminded him of the work of contemporary artist Sue De Beer, whose photographs Issue Magazine called, “a mature reflection on the complex interior lives of disaffected suburban American teenagers.”

Stewart’s music is animated by similar themes. Observer wrote of “Stewart’s sense of social detachment, of morose reflection and self-imposed exile.” Likewise, he tells me on the phone: “The stories in this record are about people […] in small places. And your room is your own personal, small place where you can listen to music and you’re not going to be distracted.” Accordingly, Stewart sees his work as bedroom music—despite that I think it’s perfect for driving around Los Angeles at night (the Internet mistakenly believes Black Marble’s 2012 single “A Great Design” is on the soundtrack to Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive).

Stewart has a precise idea of how he wants his music to be consumed. He doesn’t imagine people blasting his music on the radio or at a bar. Rather, he envisions consumers listening to his tracks in their bedrooms while reading or flipping through a book of art, lingering in a relaxed state. He gets caught up in the sound (he does all the mixing himself) because he wants to transport listeners into a “weird alternate reality where things are simpler,” in which he or she “hopefully gets lost.”

Specifically, he imagines a scenario “where it takes you a few songs to sink into the mood of the record, and then you’re in it. And when it’s over, you have to kind of be snapped out of it.” He pauses. “Like a movie when the lights turn on.” This analogy is apt as Stewart’s music has an undeniable cinematic quality (hence the Drive misunderstanding). In fact Stewart recently moved to LA from Brooklyn, leaving his job in advertising, to pursue film scoring as a side job.

“Who would be your dream filmmaker to score for?” I ask.

“Well, Chris Marker,” he says of the avant-garde French filmmaker. “But he’s dead.”

In the realm of feasible possibilities, Chris would most like to score experimental, indie horror films that have recently seen a resurgence in popularity, citing It Follows as the paragon. Both the 2014 David Robert Mitchell film and Black Marble’s music have been linked by critics to the aesthetics of another time, most frequently the 1980s. Grantland wrote of It Follows that “the film is imbued with a not-quite-antique aura,” explaining that it’s glossed in an “’80s sheen.” Likewise, Vice wrote that “Frisk“—the first single off It’s Immaterial—is decorated with “deliciously nostalgic ’80s synths.”

Stewart tells me on the phone that he aims to make a sound “you can’t quite hear.” He continues, “like when you hear something and it sounds amazing and you wish you could hear it better, and the fact that you can’t is part of why it’s so good.” Accordingly, Black Marble often sounds like something from the distant past, evoking a vague wistfulness that’s difficult to articulate. Stewart told his label, Ghostly International, that It’s Immaterial reflects “a lot of psychic turmoil about time, place, and the dissatisfaction that comes with being young and not having control over place, or being old and not having control over time.”

Chris Stewart AKA Black Marble

The name Black Marble itself is in fact derived from another time, referencing the popular ‘80s design trend. He sees the material as a “solid representation of the way things come can go.” He goes on to imagine a 1980s New Yorker “working finger to the bone for material possessions,” decorating his entire Upper East Side brownstone exclusively in the black marble, only the material to be seen at “totally tacky” ten years later.

“That’s kind of sad,” I say.

“I mean it with a bit of humor,” he says, and I think of a dumb pun—It’s Immaterial.

Stewart tells me that people say his newer tracks sound “warmer and more immediate,” and tend to attribute it to his move from Brooklyn to sunny Los Angeles. Stewart assures me his move is not responsible for the music’s change in sound, particularly since he wrote most of It’s Immaterial while living in Brooklyn. Rather, the album’s warmth can be attributed to the fact that Stewart simply wanted to challenge himself to do something different. His earlier music is drenched in reverb, which he says is an easy way to make music sound good. With It’s Immaterial, he wanted to push himself to experiment with pop structures, with making melodies that “get in your head.”

His efforts appear to have worked. The wistful melodies of It’s Immaterial have been floating around my head since I heard the album, which dropped on Ghostly International on October 14. I highly recommend you go get lost the weird alternate reality of It’s Immaterial at your earliest convenience.

***