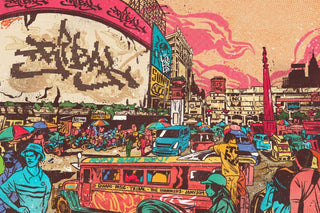

Metro Manila is a chaotic place, consumed by layers of sounds and sights all madly competing for people’s limited attention in public spaces. The capital of the Philippines is covered in signage, billboards, graffiti, wheat pasted ads, election posters and more, all piled on top of one another. And it’s only noticeable in quick glances while picking your way through tightly wound crowds and dodging the thickly clogged traffic. But one thing that stands out repeatedly, even more so than the global golden arches and the local fast food powerhouse Jollibee’s, is the Tribal logo. This Southern California streetwear brand has become a household name far, far away, in a Southeast Asian island nation on the other side of the world.

It’s worn proudly by people from all walks of life across this megacity, from workers commuting on packed trains and kids playing in the street, to grandmas and goons. Barbers wear it as their uniforms and the stickers are plastered on public transit. Tribal’s presence here far outpaces anything it ever reached back home, where it was one of the first streetwear brands ever and could be found all over the US, being worn by kids in every state. But it was never as ubiquitous as it is here in the Philippines.

So how did this happen? How did a brand that represented Southern Cali street culture and ran the nascent streetwear market of the mid-90s come to grow into the most popular clothing line on the far side of the globe two decades later?

To understand today, we need to understand the past. Tribal began in 1989 as the brainchild of Bobby Ruiz and his brother, Joey. It was a place to bring together their broad swath of interests like graffiti, tattoos, skateboarding, lowriders, rock, and hip-hop. It was rare for its time, so much so that when they showed up at their first ASR trade show in 1992, organizers had no idea where to place them. “They didn’t know what to do with us,” Bobby reflects. “We skated, but there were all these other elements, too.” It was the start of a new era, and included other brands that Bobby worked alongside like Third Rail, Con Art, Gypsies and Thieves, and Famous all coming into their own at the same time. “We stood out at the surf and skate show like sore thumbs. They would always put us right next to Stussy, because that was the closest thing to us at the time.”

“They didn’t know what to do with us,” Bobby reflects. “We skated, but there were all these other elements, too.”

And although these young brands would soon change the world of fashion permanently, they were bumping heads with the trade show organizers. “They didn’t want to give us booths and started kicking us out. Telling us to turn the music down and stop blocking the aisles with breakdancers. It wasn’t just us, it was other brands getting loud too. But we kept doing the shows despite that.” Later on, organizers would clamber over each other to get these labels into the shows, offering free booths and prime locations, but it was a rocky start. This lack of institutional acceptance didn’t slow them down, however, and the world was already hungry for what they were offering.

Tribal went international with that first trade show in San Diego, getting picked up by hip-hop boutiques in Germany and France. They were shipping to New York and Detroit, too. “What you have to remember, is that this was before the internet,” Bobby explains. “All we had was the fax machine, which had just came out. We were in skate and graffiti mags. Hip-hop rags. All paper media. We advertised in Thrasher when it was very young. That’s all there was.” And they represented a node that brought all these segmented spaces together. “We were putting out the Tribal promotional videos. There were already skate videos, but we had a lifestyle surrounded by lowriders and tattoos and graffiti and b-boys; this ethnically diverse lifestyle. These videos were the only way to see any of this in motion. People would play them at parties and clubs and skates shops.” By the age of 25, Bobby Ruiz was helping to bring an entire regional culture to the rest of the world.

With the troubles at the ASR trade shows coming to a head, the young malcontents banded together to form an oppositional show called 432F in 1994. In addition to the labels mentioned earlier, this new show featured brands from across the country like Ecko, Triple Five Soul, and Jive. Shepard Fairey and Futura were there, too. “If there was a place that streetwear was born, it was definitely there,” Bobby says.

432F is where Tribal found its way to Japan, and it would be a foundational shift for the brand. “Japan took hold of Tribal and ran harder with it than everybody. When we did our first tour there, we brought 28 people. People were tripping! We ended up doing 15-20 tours there.” While this was an explosive entry into Asia, it would still be a few years before the seed would be planted in the Philippines.

In 2003, Tribal opened their flagship store in Manila, and that shop itself played a big role in how they gained such solid roots here. Designed like a subway station with a train and platform, the concept store was a wholly new approach in the Philippines and people would stop in their tracks when they passed by. “I think we found ourselves in a position similar to how it was originally here at home, that there was nothing like us yet,” Bobby says.

“The concept stores made a huge impact for us,” says Arvin Espeleta, who is currently head of merchandising. “It wasn’t a typical thing for the Philippines at all. We invited graffiti artists like OG Able and Risk to collaborate on the glass at that first shop. The mall wouldn’t let us do it again because of the smell. They actually stopped us right as we were finishing up.” Like many other parts of Asia, malls are being built at a rapid clip here, and their first shop was located in the original SM Manila, the first mall of many to come, courtesy of the SM super chain that’s constructing them nonstop across the Philippines.

“We have 47 stand alone boutiques and are present in over 100 department stores across the country,” Espeleta continues. “We’ve got shops built to look like cathedrals and dungeons. Shops with tattoo parlors and barbers in them. Our flagship in SM Manila has been renovated four times already. But we had to educate people, because they had no idea what we were at first.” To do that, they would play the promotional videos on big screens in their stores. They had billboards and did television appearances like MTV and local morning shows. They sponsored local b-boys, including the very young Filipino All Stars, who are now one of the biggest teams in the country. They’d advertise in music magazines and give out clothes to local stars. The promotional tours made their way here too, of course, but they never reached the scale of those in Japan.

Part of the reason the Philippines may have embraced Tribal so thoroughly could be their connection to California. There are more Filipinos in the state than anywhere else in the world, other than their home country: 1.7 million Filipinos are located in Cali. That means there are more Filipinos in this state alone than the second highest country for Filipinos overseas, which is Saudi Arabia, clocking in at 1 million. The US has 4 million Filipinos total, with around 500,000 living in LA. So, that type of back-and-forth between Filipino-Americans with their relatives and friends back home is sure to lead to cultural exchanges. Chicano culture certainly has a presence here, and West Coast slang has made its way into some of their vocabulary as well.

Tribal’s involvement in local Philippine festivals may be the most lasting thing they’ve done, which not only helped cement their name here but also contributed to pushing local culture to new levels.

When I met with Espeleta, he had just finished setting up a booth at Summer Slam, a rock festival organized by the country’s longest running music magazine, Pulp. Later that night, Slayer would perform inside a stadium under a three story pentagram while flames burst high into the sky and crowds thrashed in mosh pits and massive walls of death. Bouncers from Summer Slam are outfitted with Tribal brand staff shirts and they often wear them throughout the year at other events they’re hired for. Tribal has been a sponsor of Summer Slam since its third year, and this year was the 19th iteration.

The rock element would prove to become a long lasting aspect of Tribal’s identity in the Philippines, and the label is much more associated with rock than its hip-hop roots. Espeleta traces the shift back to when Tribal began promoting rap-rock acts like Limp Bizkit and POD, and Filipinos just ran with it, never looking back at the rap portion of that mix.

Some of the younger generation that have embraced Atlanta-driven rap culture and modern streetwear seem to be less interested in Tribal. Part of that may be due to the rock-driven element, but another aspect could be the taint caused by counterfeiting. “Some of the consumers there can’t afford it though but still want it,” Bobby reasons. “In the beginning, I used to get really pissed off. You can throw a lot of money at it, but they’re like gophers. We get bootlegged hard as fuck all over Asia. But it means you’ve arrived… I guess. Not that I’m into it. It dilutes the brand.” You can find them for sale everywhere along with many other of the expected brands, even along highway overpasses at midnight in some neighborhoods.

Tribal’s involvement in the Dutdutan tattoo festival is another marker of their success. While the Philippines traditionally embraced tattoos as a part of their culture, Western colonizers stigmatized the practice for centuries, and it wouldn’t be until a few years ago that the art regained wide acceptance here. Dutdutan played a big role in that change of perception. These days, Dutdutan is a massive ordeal, an annual event bringing hundreds of tattoo artists and performers from around the world with thousands of fans in attendance. But when Rick Sta Ana started it in the mid-2000s, it was basically just a Christmas party where friends would get together to bond over tattoos and music. Tribal helped to elevate it.

“Our brand was in line with what they were doing, so we got involved in 2007. Then we had to rent a bigger place the following year to fit the whole thing. By 2009, it had gotten crazy and the scale just exploded,” Espeleta recalls. “When we saw how Dutdutan was growing, that’s when we really knew that Tribal’s influence was taking off. I mean, we played a role in breaking the tattoo taboo! Now, when foreigners come here and see how far we’ve come, they’re like, ‘Whaaaat.’ Because it’s not like this anywhere else. Even people from Tribal in Japan and Taiwan are amazed.”

Bobby says he felt the same as those visitors: “In the beginning, I was just overwhelmed. Tribal is everywhere you look.”

And it’s still like that. You can go to a beach far from the city, and a banca boat will be floating in the clear sea with a Tribal stencil. There are jeepneys stuck in rush hour traffic with three foot tall steel Tribal stars welded to their hoods. Scooters have been spotted with Tribal stickers from across the decades covering every square inch of their surface. “There are a lot of avid fans who just love the brand and want to participate,” says Espeleta. “We’re pretty happy about it.”

Original art by Jappy Lemon, for exclusive use by The Hundreds

***