I had first heard of Stranger Things through a friend. “It’s like Goosebumps for adults,” he said, “you have to watch it.” I wasn’t convinced (and I don’t like scary things), but humored him with a quick Google search, consequently stumbling across the Stranger Things poster, a highly-detailed illustration reminiscent of Drew Struzan’s iconic movie poster art for ‘80s films like the Star Wars series. I was captivated—the expressions on the characters’ faces were so diverse: power, fear, intensity, worry. The poster alluded to this deeper mystery, an entangled plotline where all these characters coexisted, without revealing the actual story. With one glance, I was hooked.

The Stranger Things poster had the same effect on me that movie posters in the ‘80s had on audiences. In a pre-internet, pre-YouTube trailer, pre-sneak peek era, the movie poster had to embody a film’s spirit, leaving just enough mystery to coerce viewers into seeing the final product. “It’s not always about just being creative—it’s all about trying to tell the story,” artist Kyle Lambert—the man behind Netflix’s widely celebrated Stranger Things poster—tells me during our interview at The Hundreds Homebase.

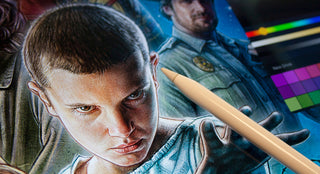

The Stranger Things poster by Kyle Lambert.

The response to Stranger Things has been nothing short of overwhelming for him, but this isn’t the first time Kyle’s work has gone viral. Although trained traditionally in oil painting, Kyle found a way to mix his love of technology with his passion for art. He has been painting with tablets for years now, always willing to share his process and encourage others to try their hand at this new wave of digital art. The video of him painting Morgan Freeman digitally has reached over 14 million views and has spurred a new appreciation for the modern art form. Kyle sees art as an experience to be shared. “The ultimate satisfaction is to hear someone say, ‘I saw your piece of work and I loved it!’ That’s kind of what it’s all about.”

Catch our conversation—musings on Drew Struzan’s legacy, how to tell if a piece is finished, and thoughts on Stranger Things (which we found out he has yet to finish!)—below.

KAT THOMPSON: I read that you were trained as an oil painter. Can you talk a bit about doing such a traditional form of art and then transitioning into digital media?

KYLE LAMBERT: I’ve basically done artwork my whole life. You start off drawing with crayons and pencil and things like that. Through art school, I’ve learned more techniques through traditional training that you get in school. As I left school to go through university, I’ve always selected art. I got to the point where I was starting to focus on portraits. At the time, I was still just using pencil. One day, we had an oil painting class and I completely fell in love with the idea of being able to paint color in the same way that I could do pencil and being able to do it in a realistic way. I got really into that and learned about mixing colors and doing big canvases and things like that.

At the same time, I was getting really interested in technology. I bought my first Mac and started using that to do things. I had used Photoshop a while back for doing very simple graphics and scanning in comic book illustrations and then coloring them. And then one day I just connected the dots and realized you can do the whole thing—you didn’t have to sketch it first. It was when I bought my first Wacom tablet that I realized you could do both in the computer. That was the moment really—when I got the Wacom tablet. I just started with a blank canvas and began painting portraits. Basically all the stuff I learned while painting became relevant in the computer and I just figured out how to make paint brushes that looked oil paint-ily. I got really interested in photorealism and started learning how to paint things that look realistic. Simultaneously, I was in university learning about illustration and about storytelling and that’s been the next tangent I’ve gone off in now.

Do you feel like the traditional art world of fine art and painting judges digital art?

In general, it depends on what idea you’re trying to be. A lot of people look at digital artwork and say it’s not art. When they mean art, they mean the kind of art that you would have hanging in a gallery. And of course it’s not going to be hung in a gallery because it’s in digital space. It all depends on who’s doing the work and the purpose. I do mostly commercial work and they don’t want me to submit oil paintings—they want me to submit digital files that they can manipulate and change. So for me, it’s always made sense to stay in the digital space. My end goal is not to be hung in a gallery, it’s to see artwork shared around the world and the commercial space is a great way to do that... As an artist, you want your work to be seen and it’s a great platform for that.

I was doing a lot of digging in your social media and what not, and in 2012 you said, “Working on personal projects can be very enjoyable, but creating artwork for others and seeing their reactions has to be ultimate.” Do you still stand by that?

Yeah. I mean, everyone loves creating artwork and doing their own thing, but it goes back to that idea when you were a kid and you draw something at school and you come home and your mum would stick it on the fridge; there’s a part of that in every artist. Every musician wants their songs to be heard, everybody who makes a movie wants it to be seen by people. It’s the same in the art world. The ultimate satisfaction is to hear someone say, “I saw your piece of work and I loved it!” That’s kind of what it’s all about.

Moving more into Stranger Things—what was it like when Netflix first reached out to you? What was your initial reaction?

It was actually a design agency called Contend that reached out to me that Netflix had hired to do the project. They basically gave me the loose brief of what they wanted and we began sketching ideas. They gave me feedback and I gave them feedback and we passed that on to the studio. It was a very collaborative thing between the Netflix people, the filmmakers, and the agency that was working with the art directors. Over the course of maybe two or three months, we really honed in on what the design of the poster should be. I got to watch a few episodes and see stills from the show. Once we decided on what the poster should look like, I was basically let loose to create a very finished version of that.

They wanted to really pay tribute to the ‘80s style of movie poster, so I did a lot of research on some of the key artists of that period—Drew Struzan being one of my favorites, and a couple other of the key artists of that period. Basically, I did maybe three or four different tests to figure out what that style could be. I was actually hired by the directors also to do canvases that we would then give to the cast members as gifts. And during the process of creating those six canvases, I was really able to practice the style. By the time I got to the last one, I was ready to paint the poster. The final poster took maybe three weeks to do.

Did you feel like you had a lot of creative freedom or agency working with them?

Very much so. It’s not always about just being creative—it’s all about trying to tell the story. That’s the key thing with the poster. You want it to be relevant and actually convey the story, but not necessarily tell you the whole story. It’s just a real challenge to take an episodic idea but condense it all into one image. Not only do that, but make it so that it appeals to people and makes people want to watch the show, [yet] isn’t too revealing. From my perspective, as a piece of art, there’s a lot of levers to dial in. The idea is to get it as close so that it matches all those directives—it’s a great piece of art, it tells a story, all those kinds of things.

How do you feel like you approached that storytelling aspect? I was reading about how movie posters evoked so much feeling back in the ‘80s because we didn’t have social media or the internet to watch the trailers, so you wanted to pique the interest of your audience right away. How did you evoke that feeling or tell that story, alluding to the mystery and suspense of the show, without being revealing?

I think there used to be a lot more emphasis on movie posters than there are today because people used to [go to] the movie theater and look at the posters on the wall and say, “I want to see that one.” There was a lot more emphasis placed on the artwork, capturing what that movie was so that someone knew what they were going to go in and watch. I think now, like you said, there’s a lot more trailers, articles written up, a lot more reviews. But it’s still—especially on platforms like Netflix—it still boils down to people flicking through a bunch of thumbnails and deciding what they want to watch. I just love movie posters and have spent a lot of my childhood looking at them on VHS tapes. Even today, it’s an art form and there’s a lot of history to it. Essentially, I tried to channel all that knowledge and my appreciation of art, not only into a good tribute to what the past represented, but also to make something new and modern that would capture a new audience as well.

You definitely captured the ‘80s vibe of it, but it is modern and enticing in a different way.

I’m going to have my own taste as an artist. I must have a more modern taste because I’ve grown up in this era. I like graphic art. I don’t mind photo photography based posters—there’s a need for those. I like comic books, I like oil paintings. I draw inspiration from everything. I actually have a library full of images I collect every single day, categorized by different types of art—illustrations, graphics, typography, everything. When a project comes along, I can flick through all my inspiration and figure out what’s most appropriate. That’s kind of the recipe for whatever project comes along.

Why do you think someone like Drew Struzan has such a long-lasting legacy that is still affecting us today in the way we look at movie posters?

I think people just love that style of art. A lot of people don’t connect with art that you just walk into a gallery and see on the wall. When it has a contemporary spin on it, it becomes a lot more appealing. He just has a really cool style. I don’t know how to answer that really. It takes an artist to create an image that has appeal, really. A lot of advertising today is done by technology experts—the people who know Photoshop inside and out. But they don’t draw and they don’t understand the power of composition. I draw, I take photographs, I’ve spent my whole life drawing. When you’ve got someone who sees the world like that, they have a lot clearer way of thinking about how to compose something like that.

How was the reaction [to your Stranger Things poster]? Did you expect the show to take off like it did, and what has the response been from people who are admirers of your work?

It’s been really overwhelming. I had never heard of the show—it was relatively new directors on the show. I got a couple episodes to watch and even then, you don’t know what people are going to respond to. I don’t think even Netflix knew if it was going to be big or not; nobody really knows. There are multi-billion dollar movies that aren’t successful, so there really isn’t a recipe. It just happened to resonate with people, which is really cool because my artwork is at the front of that. It’s a great thing for me too. Everybody that I’ve spoken to has just loved the work and there’s such a demand for prints of the thing, which I haven’t been able to figure out yet. It’s been really great and lots of opportunities have come around because of that.

Did you watch the show?

I haven’t seen all of it yet, no.

Really?! Oh, it’s so good. I watched all of it in one day.

I’ve seen the episodes they gave me and I still have to catch up with the rest of it. I haven’t stopped, work-wise, since it came out.

Do you think there’s going to be a resurgence in illustrated movie posters now that your work has kind of picked up steam?

I don’t think so. I think it raised awareness again that people like that kind of style, but it’s a very different market than what it was in the ‘80s. They don’t have to be illustrated, whereas before they did. The problem is the illustrated style evokes a sense of nostalgia and a sense of the past, and a lot of movies don’t want that. They want to seem current and modern and appeal to young people. There’s always going to be a place for illustrated posters, but I don’t think it’ll be the scale it used to be where people are thinking, “This would look better if it were illustrated,” or, “This would convey the story better if it was illustrated.” In general, I think photography is still going to lead in poster designs.

“One of the things that is key about what I do is that I really don’t settle for something if it’s not right. I don’t lie to myself like, ‘It’s okay, it’ll do.'”

I agree. It’s all about intentionality, and if you’re not intentionally being nostalgic it doesn’t typically work. But anyway, I watched your Morgan Freeman video and noticed all the details that you changed over the course of that painting. When you’re working on a project, like Stranger Things for example, when do you realize you’ve finished? When is the process over and you’re done with the work?

You just kind of know. The way that I work is that you start off a project and after about an hour, you’re basically in fixing mode. You stop constructing something and after a certain stage you’re looking at it and critiquing it constantly... You’re basically going around the poster or around the piece of artwork continually fixing things and adding things and changing things until eventually you run out of things to be annoyed about. After awhile, you go, “I’m happy with that.” Some pieces take a lot longer than others, which basically means you’ve not got something right.

Kyle Lambert

One of the things that is key about what I do is that I really don’t settle for something if it’s not right. I don’t lie to myself like, “It’s okay, it’ll do.” I never say that because it starts as a blank canvas. I can fix it because it originally didn’t exist and came into being because I did it so I can always fix things. So I end up working a lot of hours on things that I probably shouldn’t, but it always means that by the time I’m finished, I’m happy with it. I try not to let something out my door until I’m finished with it. I’ve had projects in the past where you have to give it away before you would want to and all you see when you see it placed somewhere is, “I wish I had time to fix that.” It’s the worst feeling in the world. I just don’t let it happen anymore, even if it means not sleeping. I need to get it to the point where I’m happy with it. So that’s essentially when it’s done—when I’m happy with it. There has been many a time where I’ve put my artwork into an email and just as I’m about to press send, I delete the email, go back into Photoshop, finish it, and come back. It’s that moment when you click send and it’s no longer yours and the client receives it that I see things as clear as day.

I feel that same way as a writer. Sometimes I’ll have worked on something and feel like it’s completed, but when I reread it I know it’s not. Can you talk a little bit about that process—what are you looking towards for inspiration? Are you listening to music? What is that creative process like?

It just depends on the project. A lot of it now is client-based so I don’t really have the chance to dream up that idea, I just get a brief. I just chase after things that I find interesting. The Morgan Freeman thing came about because I’ve done a few videos online and I’ve actually met people who’ve seen those videos and decided to take up digital art. That felt really awesome that I could have an impact on one person. If I can have an impact on one person, who knows how many people I could change their lives somehow by knowing they could do this? Especially now with tablets—anyone can be an artist if they download the right app and spend enough time playing with it…

I chose Morgan Freeman as this figure that most people knew. I dedicated a month to doing it because I had the time to doing it at that point... I initially shared it with my friends online, posting it on Facebook. By the end of the day, it had reached a thousand views, and I don’t have that many friends. It had basically gone from one person and they shared it with someone else who shared it with someone else. It got a thousand views just off a couple of hundred friends so I knew I had something that was potentially going to go big. I released it the next day and it got a million views that day, and thirteen million the next day. It’s kind of just reaching fifteen now—pretty much everyone I meet has seen it, which is pretty cool. I get introduced people and they’re like, “Oh! I know you!” Procreate was the number one app at Christmas that year, which basically means a lot of people downloaded that app to paint on their iPads, which essentially was the whole goal of it. For anyone who wants to do art, they have the chance to do so.

I noticed that you just recently made an Instagram and have just come back on Twitter and on Facebook. What was that hiatus like and why have you returned to social media?

Well, I just knew I had something to share. I haven’t really been doing a lot since the Morgan Freeman piece came out. I had just moved to the U.S. and life kicked in. I was busy doing life stuff, and I knew that when the Netflix project came out it would be a good springboard to start getting back into my artwork and doing more projects. It was kind of like a life break; I got married and moved and a whole bunch of things. Netflix came at the perfect time to start my career again.

***

Follow Kyle on Twitter @kylelambert, Instagram @kylelambertartist, and Facebook.

Portrait by Bobby Hundreds.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.