Last November, when artist Alex Lukas visited the national monument along the Yellowstone River in Montana, Pompey’s Pillar, he was moved by all the names carved into the sandstone rock formation, including the 1806 inscription of American explorer William Clark. “My dad and I were the only ones in sight,” Alex explains, “but we were surrounded by the evidence of all of these people who had passed before us. It all felt very personal.”

Shared experiences are a common theme in Alex’s drawings and paintings, which often feature desolate places with pieces from the past. These remnants—such as a deteriorating wall with a name spray-painted on it or a discarded tire that an unruly tree has grown through—are “hints of habitation,” as Alex says, which connect the past with the viewer’s present experience.

“I love wandering upon initials spray-painted on a wall or a name carved into a tree,” says the artist. “Seeing ‘Johnny was here’ on a rock, you’re sharing the experience of standing in the same place as Johnny. You know that you’re looking at the same scenery and occupying the same ground even if you know nothing else about Johnny.”

It is for this same reason that Alex produces and collects zines. “Zines are such an accessible, distributable medium,” he explains. “It facilitates the presentation of work in the audience’s own space and on their schedule and that type of sharing is exciting for me.”

In addition to his interest in shared experiences, Alex talks about gentrification, his admiration for large-scale outdoor paintings, and favorite zines in the following exclusive interview with The Hundreds.

Photo: arrestedmotion.com

ZIO: You’re from Cambridge, Massachusetts. What was it like growing up there?

ALEX LUKAS: It was a pretty idyllic childhood in an ultra-liberal, super diverse city. I went to public schools with progressive, open education philosophies and well-supported arts programs. I think students from 80 countries were represented in my high school, which served everyone from children in public housing to the kids of Harvard professors. Patrick Ewing, Bill de Blasio, Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, E. E. Cummings, Click and Clack (the Tappet Brothers), and the Tsarnaev brothers all attended.

It’s interesting to visit Cambridge now, the city has changed so much. Rents and the general costs of living are through the roof. I think balancing the diversity that the city prides itself on with the realities of gentrification continues to be a struggle. I say this recognizing that in every neighborhood I’ve lived in as an adult, I’ve been the gentrifier: from Bushwick in Brooklyn to Temescal in Oakland, to Point Breeze and Fishtown in Philadelphia, to Pilsen here in Chicago. I don’t have answers for the problem, but I believe it’s important to be conscious of.

Once, in high school, I was in Maine with my parents and we met some old-time, aging hippies. They told us they used to live in Cambridge, but moved out once all the yuppies started moving in. We asked when that was and they said, “‘67.” I guess it’s all relative.

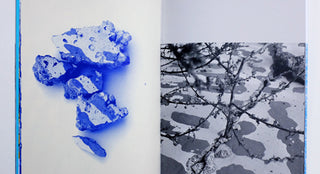

From Alex’s new zine “RSHAL backwards,” which you can purchase here.

You later moved to Philadelphia where you were part of Space 1026, and now you live in Chicago. What inspired those moves? How do you think these three places (Cambridge, Philly, and Chicago) have influenced or altered your work?

Before Philadelphia, I had been bouncing around the country. After a few years living in New York City after college, I decided it was time to try something different. So I went back to Boston for a few months, spent a few weeks in St. Louis, and then a while in the Bay Area. A studio space at 1026 in Philadelphia opened up so I moved there in 2007. I was a member at 1026 until about 2011, when I got a studio space of my own. About two years ago, I followed my partner out here to Chicago so she could get her MFA at the School of the Art Institute.

Philadelphia, aesthetically at least, has been the most influential of the three places you mentioned. It’s such an amazing looking city that has slowly and sadly fallen to where it is today. It has such a great tradition of architecture, murals, sprawling parks, public artwork, and industry, but has also been the victim of the apathy that has faced many American cities over the past 50-plus years.

I’ve also been lucky to have spent some time in Wyoming over the past few years, most recently for a monthlong residency at the Ucross Foundation. The landscape out there is almost the opposite of Philadelphia, which has influenced what I’m currently making. I hope the contrast between inspiration from the western landscape and from the architecture of the Northeast Corridor is interesting.

Who or what have been your greatest influences?

I don’t think this is the “greatest” influence, but recently I’ve been excited about the watercolors (and subsequent aquatint print portfolio) of Swiss artist Karl Bodmer. He traveled across eastern America and then up the Missouri river in 1832 to 1834 with German prince Maximilian von Wied. His depictions of the American west are really stunning. I was able to see some of the original paintings at the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, as well as copies of the print portfolio in Philadelphia and here in Chicago. I like the idea that these images were some of the first exposure easterners and Europeans had to the landscape west of the Mississippi.

There’s often a sense of desolation in your work. What do you find fascinating about desolation or desolate places?

Hints of habitation are what makes the desolation interesting to me—mysterious remnants of who and what has been there before. I love wandering upon initials spray-painted on a wall or a name carved into a tree. Seeing “Johnny was here” on a rock, you’re sharing the experience of standing in the same place as Johnny. You know that you’re looking at the same scenery and occupying the same ground even if you know nothing else about Johnny. The knowledge that even in a desolate landscape, someone else has stood here before and thought it important to mark their passage is a powerful shared experience.

The places in your works are imagined, but what real life places or things inspire these imagined places?

All sorts of places inspire the work. I’m interested in discarded structures. For example, cement relics, for which the original impetus for creation is lost, leaving only the anonymous remnant. I’ve been lucky enough to travel a lot of back roads across the country and I’m constantly pulling over and taking photos as research for the drawings. Very rarely do I actually use a photo as a direct reference for a drawing because I want the work to be somewhat universal, but I’ll incorporate a lot of the photographs into my zines.

I’m also really interested in large-scale outdoor painting like Al Loving and David Rubello’s murals from the 1970s in Detroit. I grew up seeing Sister Corita Kent’s “Rainbow Swash” in Dorchester; I thought it was so fun to look for Ho Chi Min’s profile in the blue swash. I would have loved to see Gene Davis’ “Franklin’s Footpath” in person. I think Katharina Grosse’s “psychylustro” in Philadelphia is aesthetically wonderful, but ethically problematic. These types of insertions of color and abstraction into the outdoor environment are great and I think parallel the insertion of one’s name into the landscape through graffiti, albeit with permission and funding.

What do you love about making zines?

Access. Zines are such an accessible, distributable medium and a known, familiar format for people to engage with. Everyone understands how to interact with bound paper. It’s a totally different viewing experience than visiting a gallery. It facilitates the presentation of work in the audience’s own space and on their schedule and that type of sharing is exciting for me. I think this philosophy gets tripped up a little bit when zines, inherently produced in low quantities, become coveted and fetishized art objects, but that’s a whole other conversation.

From Alex’s new zine “RHSAL backwards.”

What are a few of your favorite zines that you’ve collected over the years?

There are so many! I’ve actually been working on an archive for many of the zines and prints I’ve collected. I’m slowly photographing them and posting them at PPPRRRIIINNNTTT.com, as well as visiting other zine and printmakers to see what they’ve accumulated over the years. Dan Murphy’s Stuck On The Map has always been a favorite, as well as MEGAWORDS, which Dan produces and distributes for free with his collaborator, Anthony Smyrski. I’m happy to have some issues of LOW TIDE by CF from the early 2000s. Lief Goldberg’s NATIONAL WASTE, also from Providence around the same time, is another favorite.

Many years back, someone gave me an old issue of a zine called Albuquerque Aerosol that Mike Giant put out way back when. It’s got updates on who’s up in the city and what spots are hot; it feels really innocent and very personal. I’ve never even been to Albuquerque, but it’s a great document of a very specific time in and a very specific means of communicating within a very niche subculture.

What is your best piece of advice?

Reconsider New York City as the only destination for young artists. I think that the value of living in other cities is underrated.

::

Follow Alex Lukas on Instagram at @alexlukas and on his website alexlukas.com.