I suppose when I first started writing about fashion some years back for Hypebeast, it felt like a totally foreign world despite wearing the same clothes and being influenced from the same bouts of popular culture from the mid-‘80s and ‘90s that everyone else was. For me, approaching it like everyone else didn’t work because I needed to understand trends, brands, and influencers in a way that made sense to me. Slowly but surely, I began to understand that my need to place things in a certain context was very similar to the narratives that designers and creative directors used to inspire their seasonal offerings. Whereas I tangibly try to create a narrative with words—inspired by pictures—designers had the task of using their visuals and products to move me.

I’ve always been a fan of the movies. Hell, it’s what brought me to LA like 95 percent of the other people who reside in this smog-filled city whose layer of pollution sometimes feel like the thought bubbles of the people intent on making it. When the editors here broached the topic of marrying fashion and cinema, I jumped at the opportunity. Here are 10 movies I feel have had a huge impact on the streetwear world.

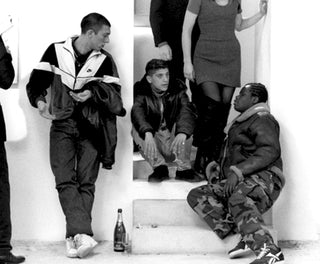

La Haine (1995)

In a day and age where nothing receives universal praise, there’s something to be said about French film La Haine which has received a 100% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Director Mathieu Kassovitz’s Parisian drama hits the senses—channeling the sights, sounds and smells of a hidden Paris—with a bullet train, in a similar vein as Spike Lee’s ode/slap in the face to New York City in Do the Right Thing (1989). While the mere mention of the “City of Light” brings to mind a certain romanticism, La Haine focuses on the restless youth and the varied struggles encountered while living in a housing project (ZUP – zone d’urbanisation prioritaire). Layered, multi-cultural and at times feeling like it was ripped from today’s headlines, ultimately it skews from the tongue in cheek tag line on the poster (“jusqu’ici tout va bien” or “so far so good”) and really aims for an authentic narrative in a place more people equate with “love” than “la haine.” As Roger Ebert put it, “If France is the man falling off the building, they are the sidewalk.”

Aside from the story and the ensemble, it’s hard to deny La Haine’s ultra-stylish wardrobe. If the film is one part break-up letter to the city, than it’s also a love letter to ‘90s streetwear silhouettes—highlighting things like Carharrt, five-panel caps, and understated windbreakers.

Stand by Me (1986)

While it may seem esoteric, if there is one thing to draw from contemporary streetwear culture, it’s the notion of the “journey.” With more tools than ever and a D.I.Y. work ethic that seems to be the new golden rule, everyone in the industry seems to be at various different mile markers—all looking to avoid that proverbial “dead end.” At its core, Stand by Me is marketed as the quintessential road trip film, tangibly moving and with an explicit goal for our four unlikely heroes. Additionally, the word “collaboration” has become synonymous with the sartorial medium. Because likeminded partnerships often breed the best results—whether they’re the intended results or not—teaming up remains one of the surefire ways to inject life in a sometimes morgue-air quality sector. While brands are seasons and even years ahead when it comes to planning apparel, ultimately they can’t force the consumer to take a ride with them.

Kids (1995)

Larry Clark’s films are lauded for a certain authenticity that peels back layers of society that make even the most voyeuristic individuals cringe simply because he’s unwilling to give you what you want. The pre-Giuliani ‘90s were a golden era for hip-hop, skateboarding, and indie rock. Using those subcultures and the excess that can permeate them as a backdrop for a narrative crafted by a then 18-year-old Harmony Korine, it seems surprising that Korine has gone on record as saying, “It was not a movie I was dying to tell.” Kids is not popcorn fare, it’s a flare gun to the temple and has documentary qualities for those who can recall popping in the VHS tape and witnessing events that rocked their suburban enclaves.

A general screenwriting rule suggests, “Write what you know.” In streetwear, personal influences from creatives and designers are of extreme importance because apparel is every bit about selling a story as it is about highlighting a quarter stitch. Look no further than The New York Times expansive profile on James Jebbia and Supreme—specifically 1995—as proof to why Kids remains so important: “Supreme felt like Kids in real life.”

Boyz in the Hood (1991)

It’s certainly not a new notion that fashion is reciprocal and that trends of yesteryear— whether good or bad—ultimately return in one form or the other. Inspiration is cultivated, and John Singleton’s slice of Los Angeles life was certainly a driving force in the retro sports movement of years past. From team-centric or regional snapbacks to baroque prints seen on the latest Foamposite collabo to even a hint at the “jogger phenomenon,” the Boyz in the Hood influence on streetwear registers more like a commandment than a simple homage.

Drive (2011)

Ryan Gosling’s titular role of “The Driver” and his “cup-runneth-over with revenge” is best personified by his blood-stained, satin scorpion bomber jacket. The classic MA-1 style—originally designed for pilots by the Air Force—in an array of colors and fabrications, is a staple piece for most if not all established and burgeoning brands, including Schott NYC, Saint Laurent, Our Legacy, Haider Ackermann, PS by Paul Smith, and Scotch & Soda. In an interview with GQ, Drive costume designer Erin Benach said, “Ryan was really inspired by these Korean souvenir jackets from the Fifties. We got to this idea of a white quilted satin jacket with a scorpion on the back. The scorpion came a little later – that was inspired by this Kenneth Anger video Scorpio [Rising]… We built the jacket from scratch. We used a tailor in Los Angeles: Richard Lim of High Society. He was really wonderful – he was able to work with the satin and used real wool for the cuffs and the collar.”

In addition to the piece everyone immediately thinks about, Gosling also sported the Levi’s Slim Fit Trucker, henleys, and Stacy Adams boots indicative of Desert stylings and chukkas that show up every season.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986)

Truer words haven’t been spoken in a movie than Ferris Bueller’s: “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” Directed by philosopher of adolescence, John Hughes, the film serves as a reminder that simple choices can have profound impacts. As Ferris, Cameron and Sloane zig-zag through Chicago—enjoying things like the Sears Tower, the Art Institute, the Board of Trade, a parade down Dearborn Street, architectural landmarks, a Gold Coast lunch and a game at Wrigley Field—their day of cultural osmosis seems to be reminiscent of narratives that brands try to present to their audiences. It’s not enough these days just to make cool clothes. Rather, there has to be a story and a laundry list of inspiration points that went into presenting it to the marketplace.

Scarface (1983)

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then parodying something is akin to asking for an item of popular culture to become a blood brother. Scarface is the type of film that transcends mediums—perhaps more famous for its one-liners and attitude than as an actual piece of cinema. The rags-to-riches story had been told countless times prior to the film’s release, and Al Pacino’s portrayal of Tony Montana was over-the-top, unapologetic, and contained a certain amount of self-awareness. Parody in streetwear remains a seemingly never-ending ploy to marry audiences. Whether that be attaching oneself to a high-fashion brand like COMME des GARCONS or making reference to a film like Jaws (1975) , reappropriation lies in being clever and original without alienating the original source material.

Shaft (1971)

It’s no secret that leather is becoming an integral fabric for brands regardless of the season or silhouette. Brought to further prominence by the likes of En Noir, Black Scale and others, the nature of the fabric immediately lends itself to monochromatic ensembles that are enjoying their own renaissance as well.

Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

Despite starring in only three films in his career, James Dean remains a style icon and served as one of the first movie stars whose wardrobe differed significantly from that of those with more “parental sensibilities.” Sporting Lee 101 Riders with a white tee and work boots as well as the iconic, red blouson jacket, he and costumer Moss Mabry changed fashion forever with a sense of style that is timeless. For the first time, dressing down was suddenly more favorable than dressing up. Additionally, what appears to be a simple piece was actually more intricate than it appears, with Mabry noting, “Even though the jacket looked simple, it wasn’t. The pockets were in just the right place; the collar was just the right size.” That same seemingly effortless look with expert construction is what everyone—whether on the brand or consumer side—is striving for. Who knows if it would have taken off like it did had the studio released the movie in black-and-white like they planned.

The Breakfast Club (1985)

The mere mention of The Breakfast Club brings with it images of varsity jackets, plaid shirts, thermals, and aged denim. Thematically, the grouping of characters who seemingly have no shared interests or differing perspectives is the perfect embodiment of contemporary streetwear. Whereas high-fashion houses continue their dominance due to their financial exclusivity and seemingly unquestioned legacy, members of the new school of fashion use that feeling of being excluded as a means of changing the status quo.