From our perch in the present day, it’s all too easy to blindly accept the numerous revisions made in cultural history. The list of bands, books, and films presently lauded as important, yet were actually crapped upon by the masses and understood by a select few during their heyday is bountiful with everything from the Velvet Underground to Caddyshack being prime examples of this phenomenon. Released fifty years ago in April of 1968, director Stanley Kubrick’s bewitching Science Fiction opus 2001: A Space Odyssey could be seen as a progenitor of this trend, considering how badly it was originally received. Panned by mainstream publications at its kickoff, the film got a sudden second wind when it was championed by the then-burgeoning underground press due to 2001’s tripped out visuals and the layers upon layers of profound meaning to be found while under the influence of the right substances.

Coming off the overall triumph of his Cold War satire Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Kubrick was given carte blanche by MGM Studios to develop whatever film he wished to make as its predecessor. Looking to make a Science Fiction movie which broke away from the genre’s typically campy nature of the time, he decided to collaborate with renowned Sci-Fi novelist Arthur C. Clarke on the film’s screenplay and development.

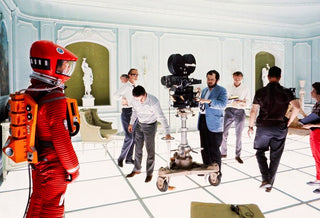

When the two men began work in the spring of 1964, the titles Tunnel To The Stars and Planetfall were bandied about until Kubrick himself came up with 2001: A Space Odyssey a year into the writing process.* When filming began at the tail end of 1965, the duo’s ambitious vision was to make a movie that was both visually stunning in its futurism as well as a metaphysical meditation on the intentions behind humankind’s determination in finding existence on other planets. In attempting this herculean effort, they managed to go four and a half million dollars over their initial six million dollar budget and a year and four months behind schedule.

Photo: hollywoodreporter.com

Finally in the spring of 1968 after four blown release dates, a last minute change in soundtrack, and countless retakes done right down to the wire, MGM was geared up to finally premiere this celluloid money pit in hopes of making back the fortune they sunk into it. First reactions to the film at the premieres in Washington, D.C., New York City, and Los Angeles did nothing to calm the studio executives’ nerves as throngs of industry types and film critics walked out of the theatre well before 2001’s conclusion.

Where Kubrick’s previous film was a sharp, dark comedy rife with out-front jokes and memorable lines served up in one hundred minutes, 2001 was a meticulously built, slow-paced Sci-Fi head scratcher sprawling over two hours and forty-one minutes. Noted film critic Roger Ebert attended the film’s premiere in L.A. and reported seeing Hollywood heartthrob Rock Hudson walking towards the exit mid-screening, muttering, “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?”

2001: A Space Odyssey movie premiere at Loew’s Capitol Theatre in New York City. Photo: in70mm.com

Photo: imdb.com

Although Ebert loved the film, many other film critics from the established media had little patience for it. The New York Times’ Renata Adler wrote that the film was “somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring” while *Joe Morgenstern of Newsweek nitpicked over the special effects calling them “obscure enough to be annoying; just precise enough to be banal.” Kathleen Carroll of the New York Daily News cynically opined, “A small sphere of intellectuals will feel that Kubrick has said something, simply because one expected him to say something,” closing off her review with, “Most moviegoers will only wish that Mr. Kubrick would come back down to earth.” Joseph Gelmis of the Long Island-based daily newspaper Newsday pulled no punches in calling 2001 “A spectacular, glorious failure.” Though Kubrick fired back at the critics calling them, “dogmatically atheistic and materialistic and earthbound,” the reviews shook him enough that he hurriedly excised twenty minutes from the film, hoping to appease those brave enough to see the film even after all the lousy reviews were heaped upon it.

Stanley Kubrick and William Sylvester, the actor who played Heywood Floyd. Photo: reddit.com

A few weeks after the film’s less-than-stellar premieres, positive reviews started to bubble up from the new vanguard of publications in the hippie underground. Staffed by a younger generation of writers adept in the new wave of Science Fiction writing by Michael Moorcock, Harlan Ellison, and Ursula Le Guin, as well as having the resolve obtained from the use of cannabis and psychedelic drugs, these broadsheets championed 2001 when the older, square journalists simply didn’t understand it. Perhaps at the forefront of this campaign was Gene Youngblood, who wrote a sprawling review of the film for the Los Angeles Free Press published on April 19th, 1968. Beginning the piece by simply calling 2001 a masterpiece, he goes on to break down the psychedelic nuances of the film before enthusiastically declaring, “Expanded cinema no longer is restricted to the underground.”

Photo: vanityfair.com

Soon after this review ran, a surge of support for 2001 came in from these clued in underground rags all around the U.S. Lenny Lipton of the Berkeley Barb echoed Youngblood’s sentiments of the movie being a masterpiece and flat out stated, “If your head is over thirty, you won’t dig it.” Wayne Scott of Atlanta’s Great Speckled Bird gushed, “No words can describe the vision of beauty and hope that is 2001: A Space Odyssey,” while The Chicago Seed’s Simon Moon might have outdone the lot with a protracted rumination on the film that tied together Native American mysticism, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, and the hallucinogenic compounds found in toadskin. Whether or not it qualifies as an actual review is still a mystery fifty years later. One of the only pieces of negative criticism 2001 received from America’s underground press was from Andrew Sarris of the Village Voice, who reneged on his review two years later after watching it “While under the influence of a smoked substance.”

Across the pond, London’s preeminent underground mag Oz—a publication steeped in militant leftist politics—fell in line with Sarris’s initial negative opinion of the film. In a review titled, “The Worst Trip Ever,” the magazine shrugged the film off as simply unnecessary space-age distraction and exhibited disgust at the film being released “in this, the year of our revolution.” Obviously ignoring the Oz’s stern words, John Lennon became 2001’s most vocal advocate in the music world when he not only claimed to go to a showing of the movie once a week in Leicester Square, but advocated a temple be erected to show it twenty-four hours a day.* It also didn’t deter a little known singer-songwriter named David Bowie from indulging in some cannabis tincture procured from his landlady and going to see the film. Leaving the screening inspired by the otherworldly images which floated above him while stoned to the bejesus-belt, he ended up penning his first hit single, “Space Oddity.” Between the reviews, the unsolicited endorsements and influencing one of the most popular songs of the next decade, the real-time dent 2001 was making was inarguable.

When the ’60s finally came to a close, 2001 had ended up earning 56.7 million dollars worldwide, showing the hand-wringing of the MGM suits to be pretty pointless as well as proving Don Chiasson right in a recent overview of the film written for the New Yorker where he stated: “Hippies may have saved ‘2001.’” But besides being a surprising financial success of an arthouse blockbuster, the film became an indispensable swath in the historic patchwork of the turbulently heady times, plus a signal to the about-face change the industry would make in their marketing plans. No longer were tucked-in parents the surefire demographic. Instead, it was their long-haired children reeking of weed and patchouli with disposable income that would be the target audience for movie studios in the years to come.

2001’s relevance sustained well into the ’70s when it became a staple of the midnight movie circuit born within that period, and to this day, the film is something of a rite of passage for any kid dipping his or her toes in the quest for heightened consciousness through chemistry. Even for those who have journeyed throughout the film countless times both sober or stoned, it still proves to be a jarring and euphoric watch, proving 2001 will forever be in the words of the Christian Science Monitor (of all publications) “The Ultimate Trip.”

***

Special thanks to the Fales Library of New York University for access to their library of underground publications of the ’60s.

The Hundreds X 2001: A Space Odyssey releases this Thursday, September 27, 2018.