“I want to show you where it all started,” Tapia tells us as he pulls his truck up to a wood-paneled house tucked in between an empty lot and a car repair shop. We’re on Rosa Parks Blvd in Paterson, New Jersey. But this is 4 Kornaz, he explains. 4K for short. There’s a couple dozen heads posted outside, and he introduces us to half, who offer some brief conversation before we go inside. There, we meet just as many people and begin the same routine until the lady who owns the house interrupts us, yelling at Tapia, “There will be no drug selling in this house!”

Tap laughs and explains that we’re interviewing him for an article about his rap music. “Not with my house looking like this you’re not,” she replies, only half joking. A little boy holds her hand, and Tapia bends down to explain to him, too. “I’m gonna be in a magazine because of my music,” he says in what feels like a quick pep talk. We give the little man pounds too and he smiles shyly.

While chatting with the guys at the table playing cards and rolling up, it’s clear that the spot is too noisy for the interview. “Aight, let’s go to Fetty’s crib,” Tapia decides. He’s childhood friends with Fetty Wap, and is signed to RGF Productions, the label that helped make Fetty famous. But Tapia also pushes SGB, or Savage Gutta Boyz, and we’re with some of them now. After taking a second to meet the rest of the homies outside, we’re back in the truck and on the move.

Before getting to the next stop, we have to track down Hunger, another rapper. After pulling up to three or four corners and asking around for him, he finally climbs in, says hello, and immediately hands out CDs of his new tape. “This the other main artist from SGB,” Tapia explains, swiveling his head back to grin at us before pulling out again.

The whole trip is very fast-paced and animated, and Tapia jumps around from subject to subject in the same manner, nearly always smiling, phone constantly in hand. He’s playing all his new music for us as loud as possible, letting us hear the material that he’s trying to resist dropping. “I got like three mixtapes ready, but I got to let the last one breathe for a bit,” he says in frustration.

The last tape he dropped was about a month ago called Radical Assumption, but he’s already posted a half dozen loosies since. He’s got a similar flow to Fetty, with a style focused on melody and harmony. This is music more in line with what’s coming out of Atlanta than nearby New York. It’s more about the way words sound than what he actually says, often built off random vowels tried out in the booth to find the right pocket, before they get turned into catchphrases and hooks.

But his flow and tone are distinct—you can easily tell that it’s his him when a track comes on. Although he layers his lyrics with countermelodies and bubbly adlibs, there’s a chanting quality to a lot of it, with repetition creating a hypnotic flavor. He also becomes increasingly cartoony, stretching out his voice out beyond reason like taffy. “It’s like anime,” he says, bouncing in the seat and pointing to the radio. This carries him towards his more pop-like corners, which is a lot brighter than usual, with higher registers and more vibrancy.

He’s in the studio twice a week, bringing with him everything he’ll need so that he won’t have to leave the session for anything, freestyling all of his tracks. It’s only been serious for him for about a year, but rapping was natural since his early years. This is “punk rap,” as he calls it, and he wants to keep making different genres. Different sounds to keep listeners on their toes. Like most artists in the area, he usually works out of nearby 934 Studio.

Exiting the dense urban streets and merging onto the highway, he flits through subjects of any nature with the same candidness. “My daddy got shot in his head in front of me when I was 13,” he reveals, 20 years old now, keeping his eyes on the road. The incident was one of many national headlines that his neighborhood has made. His father, Robert Godfrey, was manning the grill for a National Night Out block party in 2010. Afterwards he got into an altercation nearby that escalated, leading to his death. A murder had never happened during one of these syndicated events anywhere the country. But his home is a particularly violent area in an already troubled city.

Only a few months later, Tapia, whose real name is Paul Cleghorn, would also lose his brother, Ny’javar Jackson, to the gun violence that plagues the area. It was fall out from a long-running dispute between two different neighborhoods called “up the hill” and “down the hill.” “This has been going on since before we were born,” he explains with exasperation in his voice. “It was handed down to us. We inherited it.”

When I ask which side he lives on, just to try make sense of the region, he quickly points out he’s not from either. “I only rock with SGB,” he says. There are other rappers who’ve actively taken sides and used rap to accelerate disputes, but Tap is not one of them.

Despite this, the corner where we met was in the news that very day. A trial was starting for shooters accused of accidentally killing a 12 year old girl named Genesis Rincon. She died last year while riding her scooter, and was only the first of a rapid string of three young, innocent victims that led to citywide outrage. A truce between the rivaling sides was brokered as a result, and the city has seen a dip in shootings. But it hasn’t stopped the violence entirely. At least four were wounded in shootings over the past few months, including a little boy who was indoors.

“This the only thing I got that’s going my way, that I can control,” he says, pointing to the radio again. “It’s not for the money.”

Paterson, also called Pakistan or P-Town by the locals, is a city of about 150,000 people that’s only 30 minutes away from Manhattan. You can see the skyline in the distance, but it’s a world apart. Even by Jersey standards it’s overlooked. Newark, for example, has a long history of artists making names for themselves. Not so much for Paterson. Fetty’s rise is changing that. While there’s always been rappers around, they seem particularly motivated now. The Remy Boyz and Zoo Gang are especially hungry themselves, and they’re all working to put each other on.

Eventually we pull up to his mansion and park in a driveway full of rare cars and the sound of crickets. “I been living here about a year and half,” Tap says, as a pitbull greets us wagging and smiling. “Wap took me in. Opened his arms. I been learning the ropes from him. I could still be on my corner, but I’m here.”

In the basement, which is empty except for some leather couches and unused gym equipment, Tapia plays more music for us while members of his crew wander in and out. When Rome comes though, he’s three times the size of the very skinny Tapia, and we learn that he’s “the best hype man out there.” Then Tapia jumps up and starts performing for us, doing little dabs and air guitars. He loves performing. Everyone in the room seems to get excited; even Hunger, who earlier had apologized for being so quiet, is now bouncing and rapping along. “I’m not just a rapper,” Tapia says, “I’m an entertainer! A rock star. I’m tryna channel Bob Dylan, bro.”

There’s a few local spots that rappers perform at, like Bliss Lounge, Classicos, and Doctor’s Cave strip club. But he feels like he’s already performed at them too often and doesn’t do so much anymore. “I’m trying to explore and meet new people,” he says. “It’s a big world out there and there’s a lot of opportunities.”

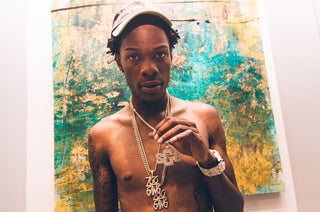

Fetty doesn’t show and we want to get some night shots anyway, so we’re off again. Before we head upstairs, Rome takes off his two Zoo Gang chains and adds them to the SBG chain already draped around Tapia’s neck.

Driving around through empty streets, they decide against the last photo shoot. It’s too exposed at night time without any of their team, even in the safer areas of the city. “I gotta keep it moving now, because people know to look for me,” he explains. The truck pulls over to let Hunger out, and before disappearing into the night, he tells Tap he loves him. A few people said it as we left each spot throughout the day. “My boys and my block,” he says. “That’s really all I got.”

***

Follow Tapia on Instagram @TapiaRGF. Photos by Gianny Matias.